Christmas, 1862

The Winter of 1862 was an incredibly challenging time for the Army of the Potomac. This period marked the replacement of their favored leader, George B. McClellan, and included the humiliating defeat at the Battle of Fredericksburg. Additionally, many officers left the army, facing the prospect of enduring a harsh winter in quarters along the Rappahannock River. The Christmas holiday of 1862 was the first one spent under difficult field conditions. Several war correspondents were present to remind the Northern public of the deprivations and hardships experienced by soldiers who, for the first time, faced the holidays away from home and and loved ones (Harper’s Weekly, January 3, 1863)

The following accounts were published in the New York Tribune, December 27, 1862

Opposite Fredericksburg

December 24, 1862

Whether or not the chief officers in command of the Army of the Potomac have received any instruction from the still higher powers that "Winter Quarters" is now to be the order, none but themselves can positively say; certain it is that the soldiers are everywhere setting upon the supposition that the "Rebs" are to be permitted peacefully to enter their occupation of the Fredericksburg Heights for some time yet. Everywhere is heard the sound of axes cutting down the sparse pine and cedar, and still scantier oak trees, that make up the thin forests of this part of the Old Dominion. Everywhere goes constantly on the work of building log huts, of putting up turf chimneys, of sealing up and roughly flooring the interior of huts, and of erecting stables for officers horses, in short, all things show that the men have resolved to make themselves comfortable in their present quarters for the rest of the winter.

From headquarters, too, come floating certain straws which are universally accepted as significant of the direction in which the official wind is blowing. Many officers have commands, and many other staff officers indispensable in case of a renewal of active operations, are said to have procured leaves of absence for a length of time that will enable them to spend the holidays among their friends at home. For the soldier, there is no leave of absence, no visit with friends, except such vicarious visiting as may be carried on in the guise of cheery, comforting love letters, which are, let us hope, more plenty at this time of year than any other - for the soldier there is little Christmas cheer: "hard tack" and "salt junk" tastes no different on Christmas Day than before or after, and if he can get a canteen of whiskey to make an evening toddy he is only too happy - let us not be too hard on him, for even such a celebration is better than none. I have, however seen pinned on one or two tents a spring of holy, in humble remembrance of the holiday which should draw all men closer together, and when loving kindness should rule over all the earth.“Many officer have procured leaves of absence for a length of time that will enable them to spend the holidays among their friends at home.”

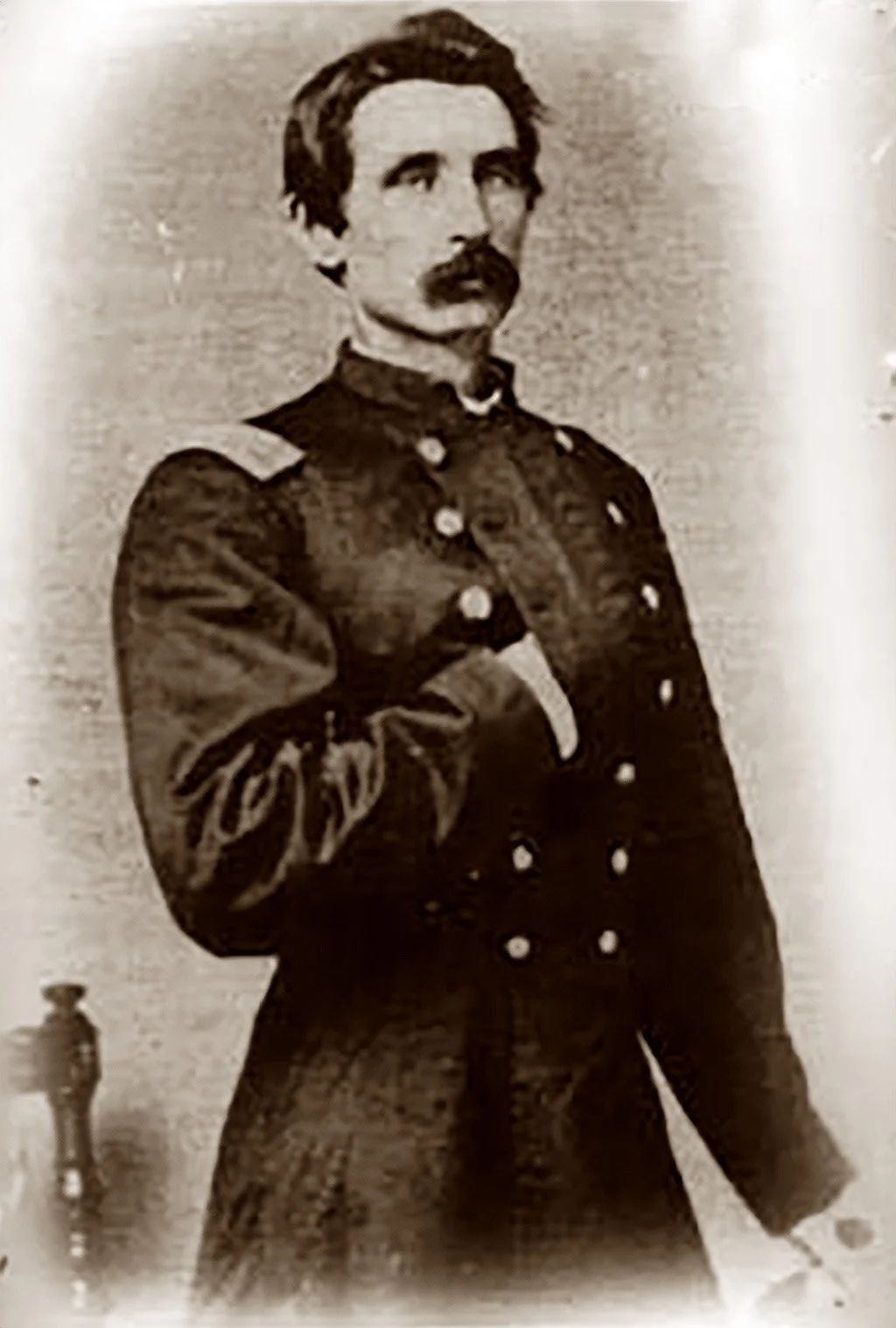

General Hooker's Central Grand Division, with which my duties specially [rise], are encamped in the same position, or very nearly so, as it occupied before crossing the river - the officers, like all the others, who can, getting leaves of absence - the men like all the others, those who must staying in camp and making themselves as comfortable as possible for the rest of the winter. No movement, and no present signs of one.The only thing that I have observed that might possibly be construed into an indication of a speedy advanced in some direction, was a simultaneous movement of the pontoon train; but it appeared to be only in obedience to an order of General Woodbury to concentrate the trains, that they may be put in perfect order, and be ready the minute they chance to be called for.There being a camp rumor that J.E.B. Stuart was about making another "raid" by crossing the Rappahannock somewhere near Deep Run, I went out of my special dominions, invaded the territory held by General Summer's Grand Division, and took a twenty-mile ride up the river to the United States Ford, and thereabout. I found the fords all guarded, and the shores of the river are vigilantly picketed by some of the regiments of General Pleasanton cavalry brigade, which consists of the 8th Illinois, 3rd Indiana, 8th Pennsylvania, 6th Regulars, 8th New York, and 6th New York Cavalry, and Pennington's Battery of Horse Artillery. The other side is just as vigilantly guarded by the Rebels, Hampton's Legion doing their duty.Colonel Richard Byrnes, an Irish-born regular army officer, was assigned to the 28th Massachusetts in October 1862. On December 13, 1862, the regiment decisively participated in the afternoon assault on Marye's Heights, where it was repulsed and nearly wiped out, enduring nearly forty percent casualties. He later fell mortally wounded on June 3, 1864 at Cold Harbor. (https://historicist.files.wordpress.com/2013/06/byrnes-richard.jpg)

Of course, as the events of the terrible battle of Fredericksburg are canvassed, hundreds of instances come to light of individual gallantry daring and coolness. Colonel [Byrnes]'s regiment of the Irish Brigade went into the fight with about 700 men and came out with 150. One after another the standard bearers were shot down, until twenty men had been killed at the duty, and the colors were torn their rags by the storm of fire through which they were so gallantly born. Seven different times did the Colonel himself seize the colors from the ground, and hand them to the nearest man. And at the last, even after all this, the colours were lost, after 500 men had fallen in their defence. After the battle, it is said the colonel sat down and wept bitter tears.

The case of a lieutenant of the same regiment is a most melancholy nature. In the advance of his regiment he was struck down by a ball, which shattered at the same time a leg and an arm; he fell between the lines of sharpshooters; he lay there for a long time suffering intolerable agony, and at last, unable to endure it longer, he drew, with his unshattered hand, his revolver, and deliberately blew out his brains.

And of many such terrible scenes in this terrible war productive, in which we are engaged, today, the holy Christmas day of the year of our Lord eighteen hundred and sixty-two. Eldridge. The January 3, 1863, issue of Harper's Weekly featured two Christmas illustrations that captured the effort to celebrate the holiday despite the nation’s struggles. On the left, there is a camp scene where the editors of the illustrated newspaper sought to idealize the hardships endured during the winter of 1862:

"In the foreground you see a little drummer boy, who, on opening his Christmas box, beholds a jack-in-the-box spring up, much to his astonishment. His companion is so much amused at so interesting an phenomenom that he forgets his own box, and it lies in the snow, unopened, beside him. He was just going to take a bite out of that apple in his hand, but the sight of his friend's gift has made him forget all aobut it. He has his other hand on a Harper's Weekly. Santa Claus has brought lots of those for the soldiers, so that they, too, as well as you little folks, may have a peep at the Christmas number. One soldier on the left, finds a stocking with all sorts of things. ANother, right behind him, has go a meerschaum pipe, just what he has been wishing for ever so long. Santa Claus is entertaining the soldiers by showing them Jeff Davis's future. He is tying a cord pretty tight round his neck, and Jeff seems to be kicking very much at such a fate. He hasn't go to the soldiers in the background yet, and they are still amusing themselves at their merry games. One of them is trying to climb a greased pole, and, as he slips down sometimes faster than he goes up, all the other who are looking at him have a great deal of fun at his expense. Others are chasing a greased boar. One fellow thought he just had him; but he is so slippery that he can't hold him, but he is so slippery that he can't hold him, and so he tumbles over on his face, and the next one that comes tumbles over him. In another place they are playing a game of footbal, and getting a fine appetite for their Christmas dinner, which is cooking on the fire."

The illustration on the right was created by Thomas Nast, who would go on to have a successful career in cartoons and engravings after the war. The wreath scene depicts vignettes of a praying wife and her husband who is missing their children. Additionally, the corner scene showcases various winter army settings.

Tobago Bay, on the Tappahannock, 30 miles below Fredericksburg,

Christmas, December 25, 1862

I am again near my old friends, the gunboats. Every time I visit them, I am obliged to go further down the Rappahannock, and I am afraid that when I am again required to seek them out, they will take me to the Chesapeake.

Searching for these little men of war in such a beautiful valley as the Rappahannock is, however, a very pleasant duty, especially as the monotony of camp leave around headquarters has again become wearisome since the late battle.

Since my last visit to Port Conway the fleet has been increased from five to nine of the largest gunboats floating upon inland waters. The guns they carry are all of the largest caliber and have been thoroughly tested in many engagements.General Lee, either fearing so formidable a foe, or desiring to capture them all in some bold night attack, concentrated a large force near Port Royal, and a few days after the battle brought two batteries to bear upon them, supported by at least one division of infantry. The weather at the same time turning excessively cold, Captain McKray, commanding the fleet, fearing that he might be frozen in, and be in danger of attack from the great superior force of infantry, fell down the river ten miles below Port Royal, to Tobago Bay, where the river is very wide, and is seldom frozen over. He is now where his transports can easily reach him throughout the entire winter and also where he can be of service to General Burnside whenever it is thought best to again move the army.

The Rebel force, stretched from five miles above Port Royal to Tobago Bay, is variously estimated at from ten to twenty thousand. The troops are nearly all from North Carolina, and under command of one of the Hills, but from which one I have been unable to learn.

These Rebel generals, I have been informed, have changed their commands lately, so that it is quite difficult to tell exactly where they are. When I left the right wing day before yesterday, I was told by a deserter that they were in front of General Sumner. Today I've been told by one of the same trustworthy persons that they are in front of General Franklin's extreme left. It is but little consequence, however, who commands these ubiquitous fellows, so long as it is certain that they are always in front of somebody and ready to fight upon the first good opportunity.“For the soldier there is little Christmas cheer: “hard tack” and “salt junk” tastes no different on Christmas Day than before or after.”

Having successfully repulsed the attack upon his center, General Lee now, undoubtedly, contemplates a movement on his right, near where General Burnside made his first feint. Rebel pickets, thinly posted, extend as far down as Urbana, and undercover of the night, cross over to this side and examine our lines. The night before last, information was received from a trusty black, who came over the river on a frail raft, that the Rebels contemplated another dash upon a squadron of the 8th Pennsylvania Calvary, who now guard the extreme advance on the left. Major Keenan had his men properly posted and would have captured the whole party had not some of them, without orders, fired their guns before the party was fairly within range.

Upon discovering that their enterprise had been divulged by someone, they sprang to their rafts and boats and reached the other side with a loss of but two or three, who were seen to drop in the river.This wood engraving was shared in the December 11, 1886 edtion of Harper's Weekly, some fourteen years after the battle. It's entitled "On the Reppahannock, Christmas Day, 1862," and was accompanied by the piece by a private of the 140th Pennsylvania recalling the incident of a short holiday truce among pickets.

One hundred head of fine, fat cattle, which had been selected with great care and purchased for the rebel army by Phelan Lewis, a wealthy planter in Westmoreland County, were yesterday seized and appropriated to the use of our own soldiers. Mr. Lewis strongly protested against the seizure, and wrought himself up to a terrible pitch of indignation on account of it, and demanded, with a very pompous manner, immediate payment or a good receipt for what he termed his private property, he received the usual receipt, with these words written and underscored beneath it: “I believe Phelan Lewis to be a disloyal man and a traitor to the government of the United States.” What would that receive be worth to those who speculate in them in Washington? Four thousand calvary, now guarding the river from six miles below Fredericksburg to Topega Bay, are subsisting entirely upon the rich planters in the valley. Not an ounce of food of any kind has been brought to them from the depot at Falmouth. Men and horses are living upon the very best the valley can produce, and I doubt if there is a table in New York on this Christmas Day covered with a greater variety of dishes than many beneath the tents and booth huts of our calvary officers. The sailors, too, upon the gunboats are really getting tipsy upon the domestic wine they have managed to get hold of by some underground transportation.In the general pillage of hen-roosts and Cellars the faithful servants, of which we hear so much, or by no means mere idle spectators. They have always been accustomed to having at least a full week for their Christmas sports and being fully aware that the 1st of January is rapidly approaching, and many of the negro huts are jubilant beyond description. Our soldiers are dining finally today, but I doubt if they are faring more sumptuously than their colored brethren. I passed a long row of negro huts upon one of old Fitzhugh’s plantations this morning and found the blacks enjoying themselves hugely, some were singing and dancing, others were eating and drinking, a few old crones, ugly as Satan, were lying in the warm sun, seemingly indifferent whether the world moved or not, but the great majority evidently knew that a better day was dawning to them and that the presence of the national army in their midst would hasten its approach.In these negro huts, all was joy, and mirth, and gladness, but in the big old mansion not far off, all was darkness, discomfort, and gloom.The proprietor was at home, but no Christmas dinner was being prepared for him. Two sons were in the Rebel army, and one in a Rebel hospital, wounded and dying. His daughters had gone within the Rebel lines upon the approach of our army. Alone he sat by his fireside, cursing his negros, the Yankees, and the world generally.Christmas of 1862 would be the final celebration with General Ambrose Burnside in command of the Army of the Potomac. The Rhode Islander was relieved of his duties on January 26, 1863. (Library of Congress)

But all these wealthy planters are not traders to the government of the United states. Several members of the old and numerous Taylor family I believe to be at heart still with us, although they have not the courage to openly avow their loyalty. Where nearly all their neighbors shipped all their slaves, who did not run away, to the South, they have not sent away a single one and have told them they were free to go north whenever they desired to. And one or two instances wages have been offered them, and the negros have promised to remain, whether the army fell back or not.What many of these planters most desire is protection. Said one of them to me today, estimated to be worth a million; “I care not under what government I live if I am only protected in the enjoyment of my property. Mr. Lincoln may emancipate all my slaves, but while doing so, he should certainly protect me from the persecution and the despotism of the southern rulers. Once assure us in this valley that your authority is to be permanent, and 2/3rds of the old Whigs will soon be with you, as they have always been .”The weather is mild and pleasant, and the troops seem to be in the best spirits. General Burnside's letter has had a most happy effect. He is more popular than ever, and whenever the soldiers catch a glimpse of him, they cheer vociferously until he has passed out of sight. I have begun to have faith in General Burnside and believe he will accomplish something great for his country.