“Welcome to These Madmen About to Die”

IN A STIRRING ACCOUNT OF THE BATTLE OF FREDERICKSBURG, LT. COLONEL DAVID WATSON ROWE OF THE 126TH PENNSYLVANIA DESCRIBES THE SHEER TERROR EXPERIENCED BY A NINE-MONTH REGIMENT OF VOLUNTEERS DURING THEIR FIRST BATTLE TEST. (The Battle of Fredericksburg, December 13, 1862," by Carl Röchling - Philadelphia Museum of Art)

The following excerpt by D. Watson Rowe appeared as “On the Fields of Fredericksburg,” in Annals of the War in 1879

Everyone remembers the slaughter and the failure at Fredericksburg; the grief of it, the momentary pang of despair. Burnside was the man of the 13th of December; than he, no more gallant soldier in all the army, no more patriotic citizen in all the republic. But he attempted there the impossible, and, as repulse grew toward disaster, lost that equal mind, which is necessary in arduous affairs. Let us remember, however, and at once, that it is easy to be wise after the event. The Army of the Potomac felt, at the end of that calamitous day, that hope itself was killed — hope, whose presence was never before wanting to that array of the unconquerable will, and steadfast purpose, and courage to persevere; the secret of its linal triumph. I have undertaken to describe certain night-scenes on that field famous for bloodshed. The battle is terrible; but the sequel of it is horrible. The battle, the charging column, is grand, sublime. The field after the action and the reaction is the spectacle which harrows up the soul.Marye's Hill was the focus of the strife. It rises in the rear of Fredericksburg, a stone's throw beyond the canal, which runs along the western border of the city. The ascent is not very abrupt. A brick house stands on the hillside, where you may overlook Fredericksburg, and all the circumjacent country. The Orange Plank road ascends the hill on the right-hand side of the house, the telegraph road on the left. A sharp rise of ground, at the foot of the heights, afforded a cover for the formation of troops. Above Marye's Hill is an elevated plateau, which commands it. The hill is part of a long, bold ridge, on which the declivity leans, stretching from Falmouth to Massoponax Creek, six miles. Its summit was shaggy and rough with the earthworks of the Confederates, and was crowned with their artillery. The stone wall on Marye's Height was their "coigne of vantage," held by the brigades of Cobb and Kershaw, of McLaws' Division. On the semi-circular crest above, and stretching

far on either hand, was Longstreet's Corps, forming the left of the Confederate line. His advance position was the stone wall and rifle trenches along the telegraph road, above the house. The guns of the enemy commanded and swept the streets which led out to the heights. Sometimes you might see a regiment marching down those streets in single file, keeping close to the houses, one file on the right-hand side, another on the left. Between the canal and the foot of the ridge was a level plat of flat, even ground, a few hundred yards in width. This restricted space afforded what opportunity there was to form in order of battle. A division massed on this narrow plain was a target for Lee's artillery, which cut fearful swaths in the dense and compact ranks. Below, and to the right of the house, were fences, which impeded the advance of the charging lines. Whatever division was assigned the task of carrying Marye's Hill, debouched from the town, crossed the canal, traversed the narrow level, and formed under cover of the rise of ground below the house. At the word, suddenly ascending this bank, they pressed forward up the hill for the stone wall and the crest beyond.Lt. Colonel D. Watson Rowe, 126th Pennsylvania courtesy of Find a Grave

“To the right, to the left, cannon were answering each other in a tremendous deafening chorus, the burden which was “Welcome to These Madmen About to Die”

From noon to dark Burnside continued to hurl one division after another against that volcano-like eminence, belching forth fire, and smoke, and iron hail. French's Division was the first to rush to the assault. When it emerged from cover, and burst out on the open, in full view of the enemy, it was greeted with a frightful, fiery reception from all his batteries on the circling summit. The ridge concentrated upon it the convergent fire of all its enginery of war. You might see at a mile the lanes made by the cannon balls in the ranks. You might see a bursting shell throw up into the air a cloud of earth and dust, mingled with the limbs of men. The batteries in front of the devoted division thundered against it. To the right, to the left, cannon were answering to each other in a tremendous deafening battle- chorus, the burden of which was:

"Welcome to these madmen about to die."

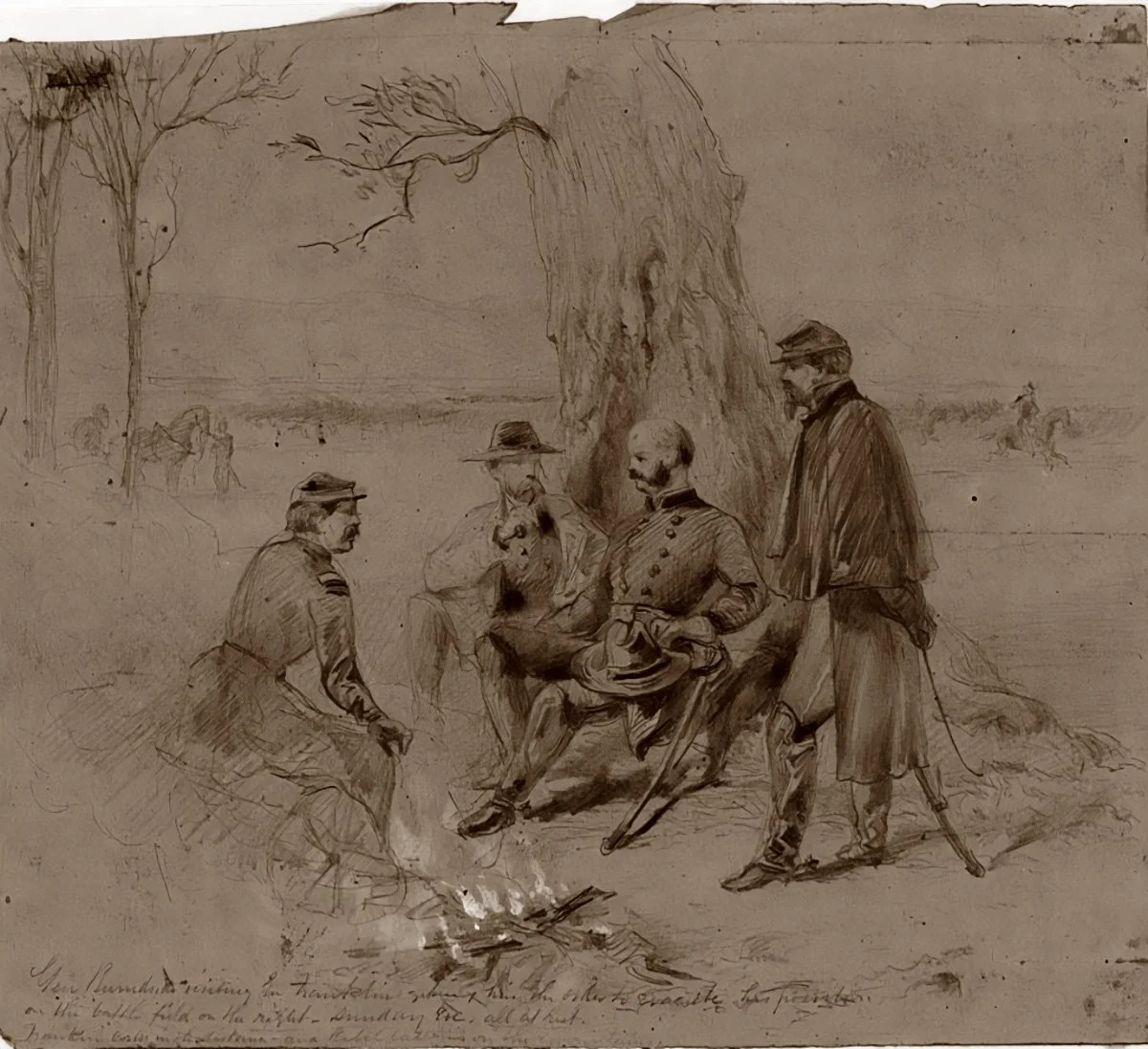

The advancing column was the focus, the point of concentration, of an arc — almost a semi-circle — of destruction. It was a centre of attraction of all deadly missiles. At that moment, that single division was going up alone in the battle against the Southern Confederacyy, and was being pounded to pieces. It continued to go up, nevertheless, toward the stone wall, toward the crest above. With lips more firmly pressed together, the men closed up their ranks and pushed forward. The storm of battle increased its fury upon them; the crash of musketry mingled with the roar of ordnance from the peaks. The stone wall and the rifle-pits added their terrible treble to the deep bass of the bellowing ridge. The rapid discharge of small arms poured a continuous rain of bullets in their faces; they fell down by tens, by scores, by hundreds. When they had gained a large part of the distance, the storm developed into a hurricane of ruin. The division of French was blown back - as if by the breath of hell's door suddenly opened, shattered, disordered, pell-mell, down the declivity, amid the shouts and yells of the enemy, which made the horrid din demoniac. Until then the division seemed to be contending with the wrath of brute and material force bent on its annihila tion. This shout recalled the human agency in all the turbulence and fury of the scene. The division of French fell back — that is to say, one-half of it. It suffered a loss of near half its numbers.An Alfred Waud drawing of General Burnside visiting General Granklin giving him order to evacuate his position on the right. (Library of Congress)

Hancock immediately charged with five thousand men, veteran regiments, led by tried commanders. They saw what had happened; they knew what would befall them. They advanced up the hill; the bravest were found dead within twenty-five paces of the stone wall; it was slaughter, havoc, carnage. In fifteen minutes they were thrown back with a loss of two thousand — unprecedented severity of loss. Hancock and French, repulsed from the stone wall, would not quit the hill altogether. Their divisions, lying down on the earth, literally clung to the ground they had won. These valiant men, who could not go forward, would not go back. All the while the batteries on the heights raged and stormed at them. Howard's Division came to their aid. Two divisions of the Ninth Corps, on their left, attacked repeatedly in their support.It was then that Burnside rode down from the Phillips House, on the northern side of the Rappahannock, and standing on the bluff at the river, staring at those formidable heights, exclaimed, "That crest must be carried tonight."' Hooker remonstrated, begged, obeyed. In the army to hear is to obey. He prepared to charge with Humphrey's Division; he brought up every available battery in the city. "I proceeded," he said, "against their barriers as I would against a fortification, and endeavored to breach a hole sufficiently large for a forlorn hope to enter." He continued the cannonading on the selected spot until sunset. He made no impression upon their works, " no more than you could make upon the side of a mountain of rock." Humphrey's Division formed under shelter of the rise, in column, for assault. They were directed to make the attack with empty muskets; there was no time there to load and fire. The officers were put in front, to lead. At the command they moved forward with great impetuosity; they charged at a run, hurrahing. The foremost of them advanced to within fifteen or twenty yards of the stone wall. Hooker afterward said: "No campaign in the world ever saw a more gallant advance than Humphrey's men made there. But they were put to do a work that no men could do." In a moment they were hurled back with enormous loss. It was now just dark; the attack was suspended. Three times from noon to dark, the cannon on the crest, the musketry at the stone wall, had prostrated division after division on Marye's Hill. The ruins of the Phillips House which served as army headquarters during the Battle of Fredericksburg. the building was set on fire in February 1863. (Photographic History of the Civil War, V. 2)

And now the sun had set; twilight had stolen out of the west and spread her veil of dusk the town, the flat, the hill, the ridge, lay under the "circling canopy of night's extended shade." Darkness and gloom had settled down upon the Phillips House, over on the Stafford Heights, where Burnside would after awhile hold his council of war.The shattered regiments of Tyler's Brigade of Humphrey's Division were assembled under cover of the bank where they had formed for the charge. A colonel rode about through the crowd with the colors of his regiment in his hand, waving them, inciting the soldiers by his words to reform for repelling a sortie. But there was really little need for that. Longstreet was content to lie behind his earthworks and stone walls, and with a few men, and the con verging fire of numerous guns, was able to fling back with derision and scorn all the columns of assault that madness might throw against his impregnable position. The brick house on the hill was full of wounded men. In front of it lay the commander of a regiment, with shattered leg, white, still, with closed eyes. His riderless horse had already been mounted by the general of the division; about him, in rows, the wounded, the dying, a few of the dead, of his own and other commands. The fatal stone wall was in easy musket range; in a moment, with one rush, the enemy might surround the building. Beyond the house, and around it, and on all the slope below it, the ground was covered with corpses. A little distance below the house, a general officer sat on his horse — the horse of the wounded colonel lying above. It was the third steed he had mounted that evening. The other two lay dead. He wras all alone ; no staff, not even an orderly. His face was toward the house and the ridge. lie pointed to the stone wall. "One minute more," he said, "and we should have been over it." He did not reflect that that would have been but the beginning of the work given him to do. He praised and blamed, besought and even swore; to be so near the goal, and not to reach it. When he saw a party of three or four descending the hill, he ordered them to stop, in order to renew the attack. After little they did what was right, quietly proceeded to the foot of the hill and joined their regiments. All the while stretcher bearers were passing up and down. Descending, they bore pitiable burdens. A wounded man, upheld by one or two comrades, haltingly made his slow way to the hospital, followed by another and another. The colonel was conveyed by four men to the town, in agony, on a portion of a panel of fence torn down in the progress of the charge. The stretcher bearers, not distinguishing between persons, had taken whatsoever one they first saw that needed their assistance ; moreover, there was no time for selection. The next minute all the wounded en the hillside might be in the hands of the Confederates.“No campaign in the world ever saw a more gallant advance than Humphrey’s men made there. But they were put to do work that no man could do.”

There was the darkness which belongs to night. The regiments had re-formed around their respective standards. They presented a short front compared with the long lines that had gone up the steep, hurrahing. The Southerners were quiet and close behind their works. It seemed that they would not sally forth. Then from each regiment a lieutenant, with a small party, went up the ascent, and sought in the darkness what fate had befallen the missing, and brought succor to the wounded. They went from man to man, as they lay on the ground. In the obscurity it was hard to distinguish the features of the slain. They felt for the letters and numbers on the caps. The letters indicated the company, the numbers denoted the regiment. Whatsoever man of their regiment they discovered, him they bore off, if wounded ; if dead, they took the valuables and mementos found on his person, for his friends, and left him to lie on the earth where he had fallen, composing his limbs, turning his face to the sky. They found such all the way up; some not far from the stone wall, a greater number near the corners of the house, where the rain of bullets had been thickest. At nine o'clock at night, the command was withdrawn from the front, and rested on their arms in the streets of the town. Some sat on the curbstones, meditating, looking gloomily at the ground; others lay on the pavement, trying to forget the events of the day in sleep. There was little said; deep dejection burdened the spirits of all. The incidents of the battle were not rehearsed, except now and then. Always, when any one spoke, it was of a slain comrade — of his virtues, or of the manner of his death; or of one missing, with many conjectures respecting him. Some of them, it was said, had premonitions, and went into the battle not expecting to survive the day. Thus they lay or sat. The conversation was with bowed head, and in a low murmur, ending in a sigh. The thoughts of all were in the homes of the killed, seeing there the scenes and sorrow which a day or two afterward occurred. Then they reverted to the comrade of the morning, the tent-sharer, lying stark and dead up on Marye's Hill, or at its base. A brave lieutenant lay on the plank road, just where the brigade crossed for the purpose of forming for the charge. A sharpshooter of the enemy had made that spot his last bed. It was December, and cold. There was no camp fire, and there was neither blanket nor overcoat. They had been stored in a warehouse preparatory to moving out to the attack. But no one mentioned the cold; it was not noticed. Steadily the wounded were carried by to the hospitals near the river. Some one, now and then, brought word of the condition of a friend. The hospitals were a harrowing sight; full, crowded, nevertheless patients were brought in constantly. Down stairs, up stairs, every room full. Surgeons, with their coats off and sleeves rolled up above the elbows, sawed off limbs, administered anaesthetics. They took off a leg or an arm in a twinkling, after a brief consultation. It seemed to be, in case of doubt — off with his limb. A colonel lay in the middle of the main room on the first floor, white, unconscious. When the surgeon was asked what hope, he turned his hand down, then up, as much as to say it may chance to fall either way. But the sights in a field hospital, after a battle, are not to be minutely described. Nine thousand was the tale of the wounded — nine thousand, and not all told.An idealistic drawing of General Humphrey’s attack at Fredericksburg, December 13, 1862. (Library of Congress)

After midnight — perhaps it was two o'clock in the morning — the brigade was again marched out of the town, and, filing in from the road, took up a position a short distance below the brick house. It was on the ground over which the successive charges had been made. The fog, however, obscured everything; not a star twinkled above them; nothing could be discerned a few feet away. The brick house could not be seen, though they were close to it. Looking back toward the town, lying on the river bank, over the narrow plain which lay below, one could not persuade one's self it was not a sheet of water unruffled in the dim landscape. Few lights, doubtless, were burning at that hour in the town. None could be seen. You would not have supposed that there was a town there. A profound stillness prevailed, broken by no other sound than the cries of the wounded. On all the eminence above, where Longstreet's forces lav, there was the silence of death. With the night, which had brought conviction of failure, the brazen throats of Burnside's guns had ceased to roar. It was as if furious lions had gone, with the darkness, to their lairs. Now and then an ambulance crept along below, without seeming to make any noise. The stretcher-bearers walked silently toward what ever spot a cry or a groan of pain indicated an object of their search. It may not have been so quiet as it seemed. Perhaps it was contrast with the thunder of cannon, and shriek of shell, and rattle of musketry, and all the thousand voices of battle.

When, on the return to Marye's Heights, the command first filed in from the road, there appeared to be a thin line of soldiers sleeping on the ground to be occupied. They seemed to make a sort of row or rank. It was as if a thin line of skirmishers had halted and lain down; they were perfectly motionless; their sleep was profound. Not one of them awoke and got up. They were not relieved, either, when the others came. They seemed to have no commander— at least none awake. Had the fatigues of the day completely overpowered all of them, officers and privates alike? They were nearest the enemy, within call of him. They were the advance line of the Union army. Was it thus that they kept their watch, on which the safety of the whole army depended, pent up between the ridge and the river? The enemy might come within ten steps of them without being seen. The fog was a veil. No one knew what lav, or moved, crept a little distance off. The regiments were allowed to lie down. In doing so, the men made a denser rank with those there before them. Still those others did not waken. If you looked closely at the face of one of them, in the mist and dimness, it was pallid, the eyes closed, the mouth open, the hair was disheveled ; besides, the attitude was often painful. There were blood-marks, also. These men were all dead. Nevertheless, the new comers lay down among them, and rested. The pall of night concealed the foe now. The sombre uncertainty of fate enveloped the morrow. One was saved from the peril of the charge, but he found himself again on Marye's Hill, near the enemy, face to face with the dead, sharing their couch, almost in their embrace, in the mist and the December night. Why not accept them as bed-fellows ? The bullet that laid low this one, if it had started diverging by ever so small an angle, would have found the heart's blood of that other who gazed upon him. It was chance or Providence, which tomorrow might be less kind. So they lay down with the dead, all in line, and were lulled asleep by the monotony of the cries of the wounded scattered everywhere.“Some sat on the curbstones, meditating, looking gloomily at the ground; others lay on the pavement, trying to forget the events of the day in sleep”

At this time three officers rode out from the ranks, down the hill, toward the town. They sought to acquire a better knowledge of the locality. They were feeling about in the fog for the foot of the hill, and the roads. After they had gone a little distance, one of them was stationed as a guide-mark, while the two others went further, reconnoitering or exploring. He who was thus left alone found himself amid strange and melancholy surroundings. Meditation sat upon his brow, but to fall into complete revery was impossible. The hour and the scene would intrude themselves upon his thoughts of what had befallen. The dead would not remain unnoticed. The dying cried out into the darkness, and demanded succor of the world. Was there nothing in the universe to save? Tens of thousands within ear-shot, and no footstep of friend or foe drew near during all the hours. Sometimes they drew near and passed by, which was an aggravation of the agony. The subdued sound of wheels rolling slowly along, and ever and anon stopping, the murmur of voices and a cry of pain, told of the ambulance on its mission. It went off in another direction. The cries were borne through the haze to the officer as he sat solitary, waiting. Now a single lament, again voices intermingled and as if in chorus; from every direction, in front, behind, to right, to left, some near, some distant and faint. Some, doubtless, were faint that were not distant, of shrieks, a call of despair, a prayer to God, a demand for water, for the ambulance, a death-rattle, a horrid scream, a voice, as of the body when the soul tore itself away, and abandoned it to the enemy, to the night, and to dissolution. The voices were various. This, the tongue of a German; that wail in the Celtic brogue of a poor Irishman. The accent of New England was distinguishable in the thin cry of that boy. From a different quarter came utterances in the dialect of a far off Western State. The appeals of the Irish were the most pathetic. They put them into every form — denunciation, remonstrance, a pitiful prayer, a peremptory demand. The German was more patient, less demonstrative, withdrawing into himself. One man raised his body on his left arm, and extending his right hand upward, cried out to the heavens, and fell back. Most of them lay moaning, with the fitful movement of unrest and pain.An early depiction of the Battle of Fredericksburg appeared in the December 27th edition of Harper's Weekly. it is meant to represent a general view of the field as seen by the reserve, the line of battle in the distancee, next to the artillery and second line of infantry.

At this hour of the night, over at the Phillips' House, Burnside, overruling his council of war, had decided, in desperation, to hurl the Ninth Corps next day, himself at its head, against that self-same eminence. The officer sat on his horse, looking out into the spectremaking mist and darkness. Nothing stirred; not the sound of a gun was heard; a dread silence, which one momentarily expected to be broken by the rattle of tire-anus. All at once he looked down. He saw something white, not far off, that moved and seemed to be a man. It was, in fact, a thing in human form. In the obscurity one could not discern what the man was doing. The officer observed him attentively. He stooped and rose again; then stooped and handled an object on the ground. He moved away, and again bent down. Presently he returned, and began once more his manipulations of the former object. The chills crept over one. The darkness and the gloom, and the contrasted stillness from the loud and frightful uproar of the day, except for the intermittent cries of the wounded and dying, groans intermingled with fearful shrieks, and cries for water, and this thing, man or fiend, hitting about on the field, now up, now down, intent on his purpose, seeing nothing else, hearing nothing, seemingly fearing nothing, loving nothing; the hill all overstrewn with dead and the debris of artillery, and mutilated horses — it was a ghostly, weird, wicked scene, sending a shudder through the frame."Who goes there?' at the length the officer said, and rode forward."A private," the man replied, and gave his regiment and company."What are you doing here at this hour?'' and so questioning he saw that the man was engaged in putting on the clothes of a dead soldier at his feet."I need clothes and shoes," he said, "and am taking them from this dead man; he won't need them anymore."''You, there! you are rifling the dead; robbing them of their watches and money. Begone!'' And the man disappeared into the night like an evil bird that had flown away.Where he had stood lay the dead man, who had fallen in the charge, stripped of his upper clothing; robbed of his life by the enemy, robbed of his garments by a comrade, alone on the hillside, in the darkness, waited for in some far off Northern home.The three officers returned to their posts. Toward morning the general commanding the brigade came out, and, withdrawing his troops a little distance to the rear, took up a new position, less exposed than the former line. The captains were cautioned to leave none of their men unwarned of the movement. Nevertheless, a few of them were not distinguished from the dead and were left where they lay. An orderly sergeant, waking from sound sleep, induced by the fatigues of the day, opened his eyes, and looked about him on all sides with surprise and wonder. His company and regiment were gone. The advance line, of which they had formed a part, had disappeared. He saw no living or moving thing. He started up and stood at gaze. What to do now? Which way to go? He concluded that the regiment had moved farther forward, and, going first to the left, and then up along a piece of fence, he saw the hostile line a short distance before him. Falling down, he crept on hands and knees, descending the hill again until he reached the road. An officer, anxious when the withdrawal was ordered that no one should remain behind for want of notice, waited until the regiments had moved away, then passed along the line just abandoned. He saw a man lying on his side, reposing on his elbow, his head supported on his hand, his left leg drawn up. You would have been certain he dozed, or meditated, so natural and restful his posture. Him he somewhat rudely touched, and thus accosted: "Get up and join your company. We have moved to the rear." The reclining figure moved not, made no response. The officer bent over him, and looked closely — he was a corpse.At length the dawn appeared — the mist was dispelled. With the coming of morning, the command was again taken into the town.