Lee’s Old War Horse Strikes Back

‘I WAS CALLED A FIGHTING GENERAL’

The James Longstreet interview

THE OLD WARHORSE OPENS UP ON THE WAR, ROBERT E. LEE, JEFFERSON DAVIS AND CONFEDERATE FAILURES

A RECONSTRUCTED REBEL

A post-war Brady image of James Longstreet. On the negative sleeve is the inscription: “Longstreet, Gen. James CSA, not in uniform, seated in Lincoln chair.”

INTERVIEWING THE GENERAL: Before releasing his 1896 memoir From Manassas to Appomattox, James Longstreet agreed to this in-depth interview by the Washington Post. The James Longstreet interview at Antietam was conducted by the Washington Post in 1893 and appeared in many national newspapers in June of that same year. The article included here was transcribed from the St. Louis Daily Globe-Democrat, June 15, 1893.

Recently, a party of ex-soldiers, composed of Gen. Heth and Col. Stearns, the Government Commission for marking the battlelines; General Longstreet and Col. Latrobe, of his staff; Maj. W.H. Mills, Mr. C. F. Cobb, one of McClellan’s scouts in the Antietam Campaign and the subscriber, visited the battlefield of Antietam. Gen. Longstreet and Col. Latrobe went up with the Commissioners to definitely settle the positions of some of the General’s troops during the battle of September 17, 1862. Notwithstanding his seventy-two years, Gen. Longstreet is clear and vigorous in mind, with a wonderful memory. Physically he is not so well off; one arm is almost totally paralyzed from the gunshot wound inflicted by his own men in the Wilderness, and, among other infirmities of old age, he is very deaf, making necessary the use of a speaking tube. His eye is clear, and his step measurably firm. He still enjoys a good dinner and is a genial raconteur in conversation. He talked to our party unreservedly on every conceivable phase of the war. He has long been engaged upon his autobiography, the manuscript of which is now ready for the printer. His visit North was mainly to arrange for its publication and for some map work. The book will be largely devoted to events in which he was an actor, including Mexican War experiences. His opinions and criticisms were so important and interesting that I felt warranted in taking them down. I subsequently asked him if he had any objections to their being printed. Deprecating my high estimate of their value, he said the world was welcome to his opinions for whatever they were worth and only stipulated for the right to revise my report. The matter used is substantially in Gen. Longstreet’s own words, and all, with the exception of the introductory, has been revised by his own hand. He made few changes. When I suggested that his somewhat harsh criticism of Gen. Early be omitted the old warrior grimly replied, “it will be in my book.” In riding to and fro over the Antietam field. Gen. Longstreet's memory was refreshed by the scene of the great battle. When the spot where the Union general, Israel B Richardson, was mortally wounded was pointed out to him, the Confederate veteran casually remarked, “There were for our side, 3 lucky shots fired on this field. I mean the ones that eliminated Hooker, Mansfield, and Richardson. They were the aggressive, fighting generals on the federal side who menaced us. After the last of the three fell there was practically an end of the serious offensive operations for the day on that side.” I was aware that General Longstreet had originally disagreed with General Lee in the fall of 1862 as to the advisability of making the Harper’s Ferry campaign, the preliminary movements of which he proceeded to explain and criticize somewhat. This led naturally to a discussion of the merits of the two commanders in the operations culminating in the battles of South Mountain and Antietam. One of our party put this question: “Do you think, General, as has been alleged, that Gen. Lee’s low estimate of the Federal commander was the reason for his extraordinary dispositions in the Harper’s Ferry Campaign?” “Perhaps so, Lee’s experience with McClellan on the Peninsula certainly must have tended to give him confidence in any collision with that officer. Gen. Lee, as a rule, did not underestimate his opponents or the fighting qualities of the Federal troops. But after Chancellorsville he came to have unlimited confidence in his own army, and undoubtedly exaggerated its capacity to overcome obstacles, to march, to fight, to bear up under deprivations and exhaustion. It was a dangerous confidence. I think every officer who served under him will unhesitatingly agree with me on this point.” To some further suggestions, Gen. Longstreet replied, “Gen Lee had a certain respect for Gen. McClellan, who had been his subordinate in the old engineers. But I judge that this feeling assumed somewhat the shape of patronage, like that of a father toward a son. He never feared any unexpected displays of strategy or aggressiveness on the part of McClellan, and in dealing with him always seemed confident that on the Federal’s part there would be no departure from the rules of was as laid down in the books.” ARTILLERY HELL

A rendering by James Hope of the Battle of Antietam where James Longstreet offered his own post-war commentary thirty years later.

“What estimate do you place upon Gen. McClellan, Gen. Longstreet? Was he considered on your side as a man of real capacity?” I asked.“At first, we were anxious about him, and the great and well-disciplined army he was gathering. But with his first operations toward Manassas and on the Peninsula his true character became manifest. We learned that McClellan was only dangerous by reason of his superior numbers. Like Gen. Lee he was greatly learned in the theory and science of war; he knew how to fight a defensive battle fairly well. But in the offensive tactics he was timid and vacillating and totally lacking in vigor. In these particulars he was diametrically the opposite of Lee. McClellan indistinctively overestimated his enemy and underestimated his own resources to meet that enemy. He was always planning, it seems to me, of the necessities in case of defeat, not with a view to victory. “Properly Gen. McCellan should have merely threatened D. H. Hill and Turner’s Pass and poured his troops through Crampton’s Gap upon McClaws’ and Anderson’s rear, with the Potomac River and the Harper’s Ferry garrison in their front. There was no escape for them, any by this movement Harper’s Ferry would have been wrested from our clutch. Instead, McClellan elected to turn northward upon us and fight at Turner’s Pass, where he lost eighteen hours, and then, after another delay of over thirty-six hours, to attack me in a chosen position behind the greatest losses on both sides. Strange to relate, President Davis held a high opinion of Gen. McClellan’s military capacity and trembled for safety of Richmond in the spring of 1862. Personally, I had not much regard for him in the field. At the very outset I predicted he would be fully a month getting ready to beat McClellan’s 7,000 men on the Peninsula and proposed that meanwhile we make a flank movement against Washington by crossing the Upper Potomac. The suggestion seemed to be offended at my cavalier opinion of McClellan.”A discussion of Antietam and Gen. McClellan without including Gen. Lee would be like the play of Hamlet with Hamlet left out. In fact, during all this talk Gen. Lee was naturally a central object of interest. In finally propounded this question to the General: A PATRONAGE RELATIONSHIP

Union Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan would lead the eastern war effort in two campaigns against Robert E. Lee in 1862. General Longstreet held a low opinion of the general.

“Gen. Longstreet, which do you consider Gen. Lee’s best battle?” " "Well,” responded the General, reflectively, “Perhaps the second battle of Manassas was, all things considered, the best tactical battle Gen. Lee ever fought. The grand strategy of the campaign also was fine and seems to have completely deceived Gen. Pope. Indeed, Pope failed to comprehend Gen. Lee’s purpose from start to finish, and, on August 30, when I was preparing to push him off the Warrenton Pike, he still imagined us to be in retreat, and his most unfortunate movements were based on that false assumption. Had Pope comprehended the true situation as early as the afternoon of August 28, as I think be ought, it might have gone hard with Jackson before I arrived. Pope was outgeneraled and outclassed by Lee, and through improper dispositions his fine army was outfought. Still, it will not do to underate Pope; he was an enterprising soldier and a fighter. His movements in all the earlier stages of that campaign were excellent for his purpose to temporarily hold the lines, first of the Rapidan and then the Rappahanock. In the secondary affair with Banks at Cedar Mountain we had gained quite a success, yet Pope promptly concentrated and forced Jackson back again over the river.”FROM MANASSAS TO APPOMATTOX

James Longstreet’s memoir, released in 1896, received mixed reviews. Despite its self-serving viewpoint, it represented the fullest defense of Longstreet’s much-maligned war record.

I said to the General that I thought the world generally would agree with him as to that campaign, and then asked him, “which of the battles he thought Lee displayed his poorest generalship?”He promptly answered, “Although it is perhaps mere supererogation to express my views, yet I will give them to your for what they are worth. I have always thought the preliminary dispositions to capture Harper’s Ferry, involving as a corollary the battles of South Mountain and Antietam, were not only the worst ever made by Gen. Lee, but invited the destruction of the Confederate army. I was opposed to the movement because his plan and the topography of that vicinity made necessary the division of our army into four parts in the immediate presence of a superior enemy. But, chiefly owing to the timidity if not incapacity of the Federal commander, and somewhat to the prestige we had gained on the Chickahominy and along Bull Run, we captured Harper’s Ferry and escaped with a drawn battle. Tactically, as usual, Lee fought a good defensive battle at Sharpsburg with greatly inferior numbers and withdrew at his leisure across the Potomac without molestation.“It was at Gettysburg where Gen. Lee’s pugnacity got the better of his strategy and judgement...” - James Longstreet, 1893

Gen. Lee displayed his greatest weakness as a tactical commander at Gettysburg, although, for the reasons named, Antietam might have been to us far more disastrous had the Federal army there been commanded by such a man as Grant. The tactics at Gettysburg were weak and fatal to success. Gen. Lee’s attack was made in detail and not in on coordinate, overwhelming rush, as it should have been. The first collision was an unforeseen accident. We did not invade Pennsylvania to merely fight a battle. We could have gotten a battle anywhere in Virginia, and a very much better one than that offered us at Gettysburg. We invaded Pennsylvania not only as a diversion to demoralize and dishearten the North, but, if possible, to draw the Federal into battle on our own terms. We were so to maneuver as to outgeneral, the Union commander, as we had done in the second Manassas campaign; in other words, to make opportunities for ourselves, and take prompt advantage of the most favorable one that presented itself. I had confidence that this was the purpose of Gen. Lee, and that he could accomplish it. We were not hunting for any fight that was offered.When in the immediate presence of the enemy Gen. Lee reversed this offensive-defensive policy - the true and natural one for us – by precipitating his army against a stronghold from which I doubt if the Federals could have been driven by less than 100,000 fresh infantry. That is all there is of Gettysburg; we did the best we could; we failed simply because we had undertaken too great a contract and went about it in the wrong way. Like Pope at Manassas, Lee at Gettysburg outgeneraled himself.”A close-up of Union and Confederate soldiers in combat at Gettysburg, July 1- 3, 1863.

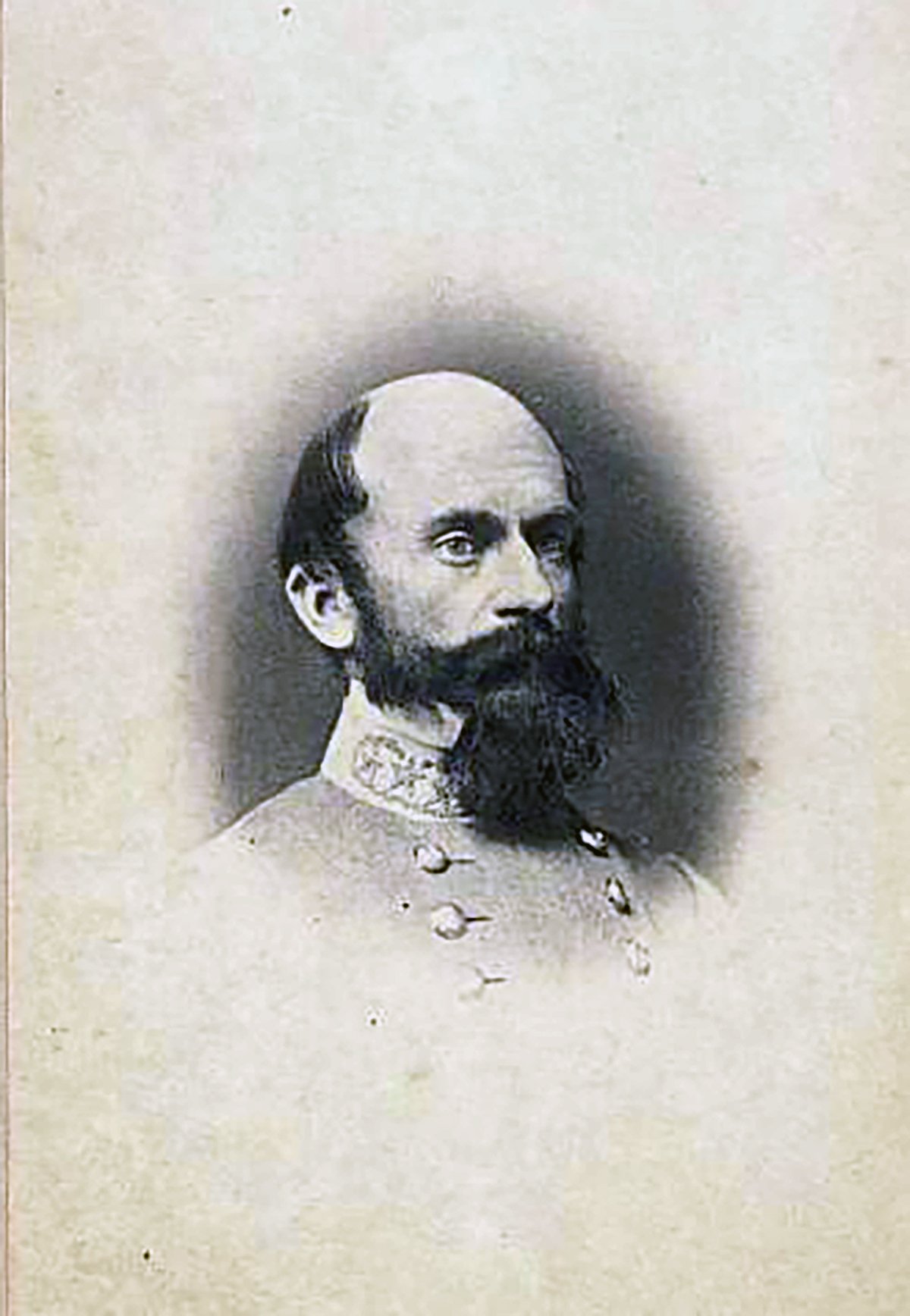

A wartime image of Robert E. Lee.

“Do you think, General, that Gen. Meade lost any opportunities at Gettysburg after the repulse of Pickett’s advance – that is to say, could more have been accomplished for the Federal cause than merely beating back your charges, and then, after the Army of Northern Virginia was exhausted, permitting it to withdraw at is leisure?”“Yes, doubtless Gen. Meade failed in enterprise at Gettysburg. Our position was made extremely perilous, projected, as we were, deep into enemy’s country, by that series of bloody repulses. After the battle our army was not only inferior in numbers, but also in morale, to the Federals. We could expect no reinforcements. Our artillery ammunition was nearly exhausted. We were in bad shape to withstand an attack. We might have repulsed a direct attack.But I think Gen. Meade should have moved by our right flank upon Gen. Lee’s communications, toward his how reinforcements, rapidly coming up, meantime still covering Washington, which, indeed, after Gettysburg was in no danger from Gen. Lee’s army. This would have forced us to again deliver a second battle on Meade’s own terms, and the result at Gettysburg is some indication of what might have happened.”In answer to a question as to what Gen. Lee’s chief attributes as a commander were, Gen. Longstreet, weighing well each word, replied as follows: “Gen. Lee was a large-minded man, of great and profound learning in the science of war. In all strategically movements he handled a great army with comprehensive ability and signal success. His campaigns against McClellan and Pope fully illustrate his capacity. On the defensive Gen. Lee was absolutely perfect. Reconciled to the single purpose of defense, he was invincible. This is demonstrated by his Fredericksburg battle, and again in the Wilderness around Spotsylvania, at Cold Harbor and before Petersburg.But of the art of war, more particularly that of giving offensive battle, I do not think Gen. Lee was a master. In science and military learning, he was greatly the superior of Gen. Grant, or any other commander on either side. But in the art of war, I have no doubt that Grant and several other officers were his equals. In this field his characteristic fault was headlong combativeness; when a blow was struck, he wished to return it on the spot. He chafed at inaction; always desired to beat up the enemy at once and have it out. He was too pugnacious. His impatience to strike, once in the presence of the enemy, whatever the disparity of forces or relative conditions, I consider the one weakness of Gen. Lee’s military character.A GATHERING OF GENERALS

Image of James Longstreet at the 1888 reunion at Gettysburg. Longstreet stands in the center beside commanders Henry Slocum and Dan Sickles.

“This trait of aggressiveness,” continued Gen. Longstreet, after a pause, “led him to take too many chances – into dangerous situations. At Chancellorsville, against every military principle, he divided his army in the presence of any enemy numerically double his own. His operations around Harper’s Ferry and Antietam were even worse. It was among the possibilities for a bold, penetrating, fighting commander like Grant to close the war in the East after Antietam. Our previous losses had been very heavy; the morale of the army was low, and it was reduced by that battle and straggling to less than 30,000 effectives, whereas McClellan had fully 80,000, quickly reinforced to over 100,000. About this time Gen. Lee officially informed the Richmond authorities of his great fear that the army was in danger of actual dissolution from straggling and desertion.”“It was at Gettysburg,” resumed Gen. Longstreet, “where Gen. Lee’s pugnacity got the better of his strategy and judgement and came near being fatal to his army and cause. On the third day, when I said to him that no 15,000 soldiers the world had ever produced could make the march of a mile under that tremendous artillery and musketry fire and break the Federal line along Cemetery Ridge, he determinedly replied that the enemy was there and that he must be attacked. His blood was up. All the vast interests at stake and the improbability of success would not deter him. In the immediate presence of the calm and clear, became excited. The same may be said of McClellan, Gustavus Smith and most other highly educated, theoretical soldiers. Now, while I was popularly called a fighting general, it was entirely different with me. When the enemy was in sight, I was content to wait for the most favorable moment to strike – to estimate the chances, and even decline battle if I thought them against me. There was no element in the situation that compelled Gen. Lee to fight the odds at Gettysburg.” The General then proceeded to discuss some of the controversies at the South concerning Gettysburg and said with some feeling that a deliberate attempt had been made by ignorant demagogues to mislead the people as to his relations with Lee at the battle and afterward. He states positively that Lee personally had never criticized or found fault with his operations in the field. A FATAL

COMPARISON

Comparing Lee’s battlefield command with Grant’s was heresy in the Lost Cause circles of the South, and James Longstreet’s temerity was not taken lightly.

I therefore asked: “I have heard it intimated, General, by some prejudiced people, that Lee, on account of coldness growing out of Gettysburg, to be rid of you, brought about your transfer to the West.”Gen. Longstreet only smiled at this suggestion, and answered promptly: “On the contrary, he was at first strongly opposed to my going, and suggested another advance into Maryland that fall instead. I first proposed going West in the spring of 1863, after Chancellorsville. I firmly believed up to Gettysburg and Vicksburg that we could win by concentrating an overwhelming force suddenly against Rosecrans. After whipping him and establishing ourselves on the Ohio, I held that the Mississippi Valley would instantly have cleared itself up to the Ohio’s mouth, as Grant would have withdrawn to defend Ohio and Indiana. This would have saved to the Confederacy some 60,000 men lost at Vicksburg, Port Hudson and Gettysburg.The proposal was coldly received by the Richmond authorities. They preferred to meet the enemy in the West with detachments, always with the weaker force at the point of contact. After Vicksburg and Gettysburg, when the darker clouds began to gather, I suggested it again to Gen. Lee, and wrote urging it upon Secretary Seddon. Gen. Lee eventually went down to Richmond up this business, and the Western concentration was finally agreed upon. Something had to be done. In fact, it was then too late; we were too weak everywhere to affect the concentration of the force I considered necessary to accomplish Rosecrans’s destruction.”FIGHTING THE ODDS

An early 20th century print showing General Pickett, on horseback, receiving orders from a resigned General Longstreet, at the battle of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, July 3, 1863.

“Every bit,” the General answered quickly and unhesitatingly. “They continued to be of the closest and most affectionate character. I was unaware of the slightest diminution of confidence in my military judgement. The friendly relations continued until long after the end of the war. My disagreement with him about some details of the Gettysburg Campaign had no more effect to estrange us than my dissent from the Sharpsburg tactics of the previous year. Instead of being discredited with Lee, he suggested to President Davis that I command the consolidated forces against Rosecrans in place of Bragg. But Bragg, probably suspected something of the kind, precipitated the battle of Chickamauga before my corps was all up. Some of Gen Lee’s original correspondence with me proves these facts beyond all controversy.”“Were the Western Confederate generals jealous of your coming, General?” I asked. “I do not think the subordinates were,” he answered, “for they to a man lacked confidence in Bragg’s skill and capacity. They filed a written request for his removal. There were evidences, however, that Gen. Bragg himself did not like my coming.”“Do you think, General, the troops you took from Virginia behaved any better at Chickamauga than the Western Confederate troops? And were the Western Federal troops you me at Chickamauga any braver than the Federals you had habitually met in Virginia?”Gen. Longstreet thoughtfully answered: “My troops were better disciplined than most of Bragg’s, but I can no say they were better fighters. I am positive that the Western Federals were no better fighters than their Eastern brethren, and they were not nearly so well disciplined.” “General, what about Stonewall Jackson? Was he as great a man as the people of the South thought?”“Jackson was undoubtedly a man of military ability. He was one of the most effective Generals on our side. Possibly he had not the requirements necessary in a commander-in-chief, but no man it either army could accomplish more than the 30,000 or 40,000 men in an independent command. But in joint movements he was not so reliable. He was very self-reliant and needed to be alone to bring out his greatest qualities. He was very lucky in success of his critical movements both in the second Manassas campaign and at Chancellorsville.Subsequently in conversation Gen. Longstreet said: “I suggested to Gen. Lee that Stonewall Jackson be sent to the Trans-Mississippi instead of Kirby Smith, as the best fitted among the Confederate generals to make headway against the Federals in that region. The suggestion met with Gen. Lee’s approbation, but Lee wanted Jackson himself.”LUCKY IN SUCCESS?

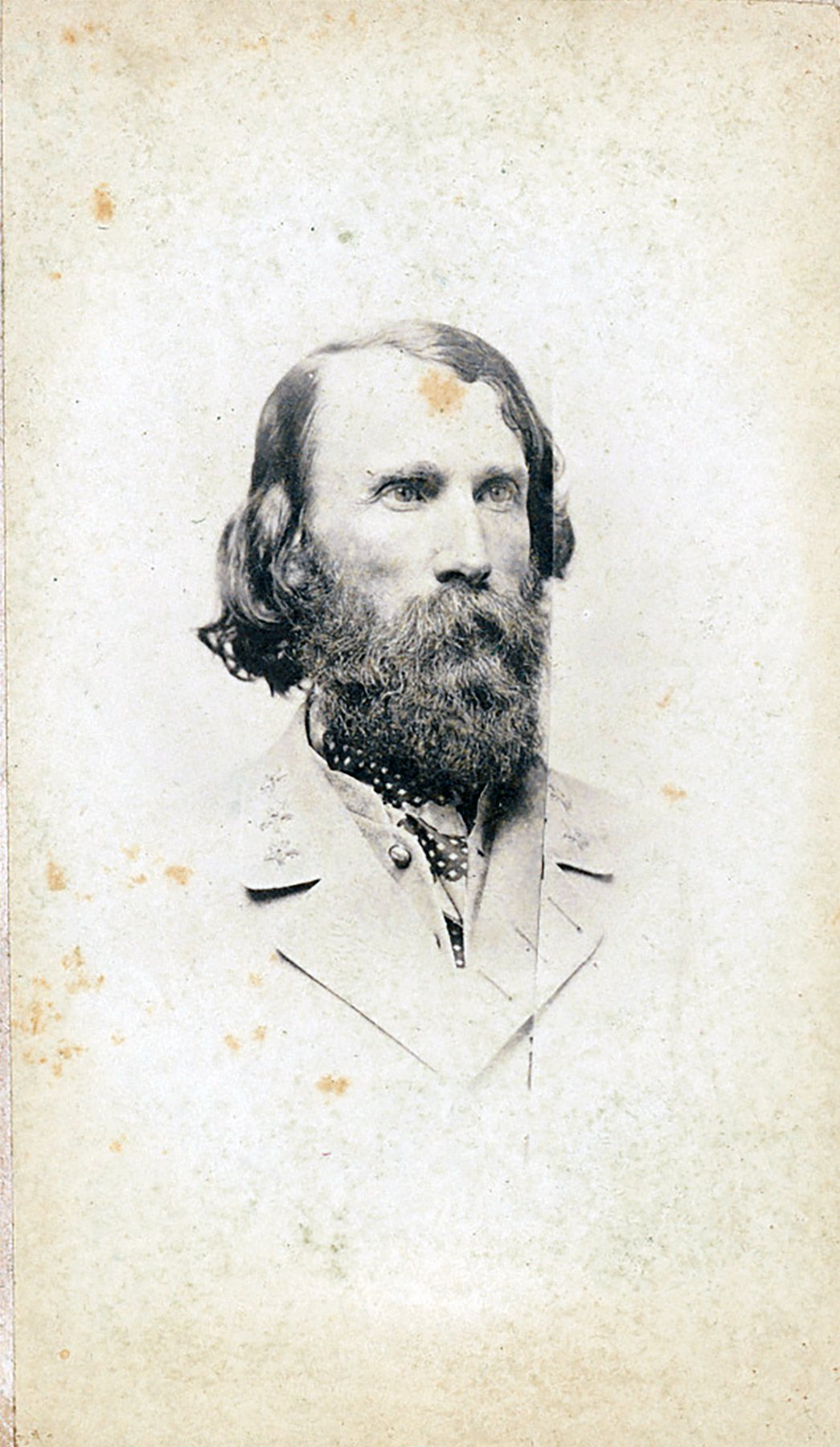

James Longstreet praised Stonewall Jackson for his military ability but doubted his reliability in joint movements. [National Portrait Gallery]

This was new, and with considerable surprise I asked: “Why did you assume that Jackson was better equipped for command in the Western country, General, than any of your other officers?”“He was the very man to organize a great war over there. He would have marched all over Missouri, invaded Kansas, Nebraska and Iowa. In fact, the very vastness of the theater was well calculated to sharpen his faculties and give scope to Jackson’s peculiar military talents. His rapid style of campaigning, suddenly appearing at remote and unexpected points, would have demoralized the Federals.”“Did Gens. Early, Ewell, or A.P. Hill size up anywhere near Jackson as leaders in independent command?”“Not by any means,” replied Gen. Longstreet. “Hill was a gallant, good soldier. There was a good deal of “curled darling” and dress parade about Hill; he was uncertain at times, falling below expectations while at others he performed prodigies. A division was about Hill’s capacity.Ewell was greatly Hill’s superior in every respect; a safe, reliable corps commander, always zealously seeking to do his duty. In execution he was the equal of Jackson, perhaps, but in independent command he was far inferior; neither was he as confident and self-reliant. Ewell lost much of his efficiency with his leg at second Manassas, and was always more or less handicapped by Early, who, as a division General, was a marplot and a disturber in Ewell’s corps.Early’s mental horizon was a limited one, and he was utterly lost beyond the regiment out of sight of his corps general. How Gen. Lee could have been misled into sending him down the valley with an army in 1864 I never clearly understood. I was away from the army that summer wounded. Early had no capacity for directing. He never could fight a battle; he could not have whipped Sheridan with Lee’s entire army. And now it occurs to me,” resumed Gen. Longstreet suddenly, “that general Sheridan was pretty lucky in his two principal opponents – Early in the valley and Pickett at Five Forks. He won his spurs without effort. Pickett was a brave division commander but was lacking in resources for a separate responsible command. Before Five Forks he expressed doubts of his own capacity to hold the extreme right and urged me to come over and take charge. I was north of the James and could not join him. I doubt if general Lee at first perceived grants object and force in the direction of Five Forks. Sheridan should and could have been met at once with half our army and overwhelmed. Pickett, with his small, isolated command, was an easy prey. Our chief fault at Five Forks was in lack of numbers. But the game was already lost. Every man lost after January 1st, 1865, was uselessly sacrificed. The surrender should have taken place certainly four months earlier than it did.”SIZING UP THE BRASS

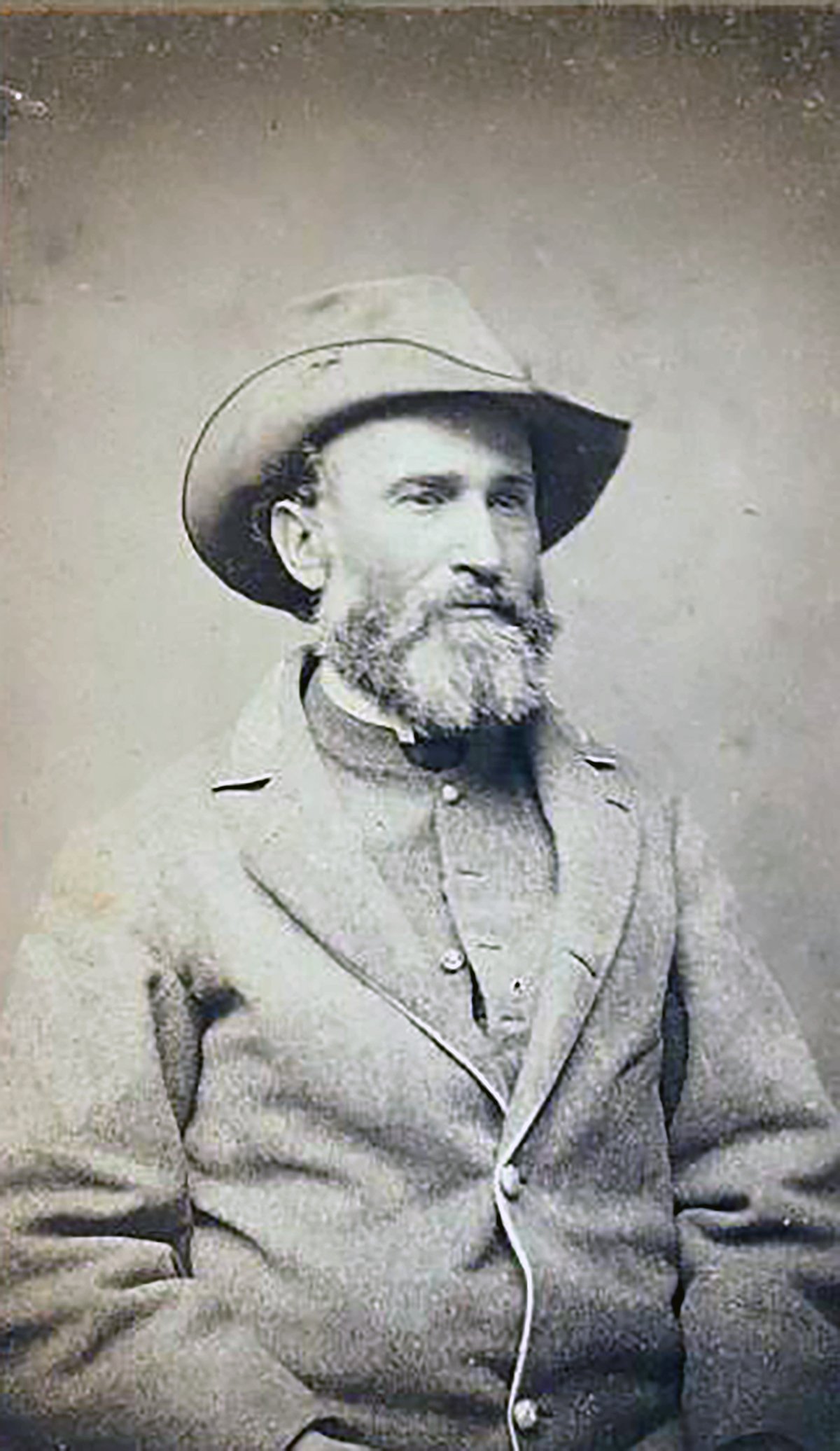

A.P. Hill (left), Richard Ewell (center), and Jubal Early (right) were corps leaders of the Army of Northern Virginia. James Longstreet had reservations about all of them. He was particularly critical of Jubal Early, who had previously blamed Longstreet for the defeat at Gettysburg.

“I have a great curiosity, General to hear your military judgment of Gens. Joe Johnston, Beauregard and Hood.”“I had a high regard for them all. General Johnston was one of the ablest generals the war produced. He could handle a large army with ease. But his usefulness to the South was greatly impaired by the personal opposition of the president. He dared take no risks on account of this “fire in the rear,” fearing that he would not be sustained, perhaps discredited before the world. A menace like that will paralyze the best efforts of any commander in the field. General Johnston never had a fair trial.The same may be said of Beauregard, a brave mettlesome soldier in action, and a strategist of the first order. He was like Johnston, equal to any command. He labored under the same disadvantages with Johnston – he had aroused the personal displeasure and jealousy of the President, and never had his full confidence. He was very resourceful, made excellent plans, and was intensely patriotic. His military suggestions received little heed at Richmond. He undoubtedly saved the capital from Butler.Gen. Hood was an officer of moderate talents and lacked experience for high command. He was a splendid fighting soldier without guile. What could have been accomplished early in 1863, as I had proposed, with a grand combined army in the West, say 100,000 men, under an able leader like Gen. Johnston or Beauregard, was demonstrated by Gen. Hood’s bold invasion with an emasculated force in the fall of 1864, when our cause was practically lost. He commanded the heart of Tennessee for weeks with less than 40,000 men.”THE MARTYR OF A CAUSE

Two guards stand in Jefferson Davis’ cell, while the prisoner sits on his bed. Inexplicably, Longstreet attributed the Confederacy’s defeat to a “lack of statesmanship” rather than the battlefield.

“Do you think, Gen. Longstreet, that the Southern cause would have been successful if the Administration had been in other hands than the hands of Mr. Davis?” I inquired.“I haven’t the shadow of a doubt that the South would have achieved it independence under Howell Cobb, of Georgia, who was a statesman pure and simple. There were others, perhaps, equally as good.The trouble with Mr. Davis was his meddling with military affairs; his vanity made him believe that he was a greater military genius; that his proper place was at the head of any army, and not in the Executive Department. He was also jealous of the success of others, especially military leaders. It is not generally known, but it is nevertheless a fact, that he was secretly jealous of Lee; that their relations were strained, and that Lee was always on his guard in dealing with the President. The world knows where the President’s attitude toward Johnston and Beauregard was – that of suspicion, opposition and obstruction. He did not venture to antagonize Lee – that officer’s prestige was too great; besides, there was no other arm on which to lean. He did not like Stonewall Jackson and called him cranky.“President Davis was not great. At one time and another he had exasperated and alienated most of the Generals in the service.”- James Longstreet, 1893

He stuck to his mediocre favorites with surprising tenacity. At the very outset he took it for granted that such men as Albert Sidney Johnston, Pemberton, Bragg, and others, without large experience were Napoleons. He could not brook criticism of his views nor of his favorites. I fell under his displeasure for saying that Bragg had failed to achieve adequate results after Chickamauga. He ought to have forced Rosecrans out of Chattanooga. This was an all-day conference between us on Mission Ridge, where the President had come after the battle.President Davis was not great. At one time and another he had exasperated and alienated most of the Generals in the service. It was lack of statesmanship that beat us, not lack of military resources; not lack of military success. We had them in equal ratio with the North, remaining carefully on the defensive. I do not admit that we were outclassed by the North. With Howell Cobb or some other good man at the head, our chances would certainly have been largely increased.The President was very unpopular throughout the South in the last days. It was clearly perceived that his administration of affairs was the chief cause of our disasters. But afterwards, the South proudly made him the martyr of the cause; before the victor they would not discredit even the man who had caused their defeat. All hearts went back to him when they saw him a prisoner and in bonds. Nevertheless, the Southern people know now as they knew then full well the truth of what I say about the President.” The James Longstreet interview at Antietam was conducted by the Washington Post in 1893 and appeared in many national newspapers in June of that same year. The article included here was transcribed from the St. Louis Daily Globe-Democrat, June 15, 1893.credits: all images are from the Library of Congress unless otherwise indicated. The colorized image of James Longstreet is courtesy of flickr/minus.com (Zuzahgaming.minus.com)