Reviewing Hooker’s Army

IN THE SPRING OF 1863, THE ARMY OF THE POTOMAC WAS RECOVERING FROM ITS RECENT DEFEAT AT THE BATTLE OF FREDERICKSBURG. THEY WERE HEALTHY AND EAGER TO LEAVE THEIR MUD-WALLED HUTS, AND THEY WELCOMED THE COMMANDER-IN-CHIEF FOR A SPRING REVIEW. ACCOMPANIED BY AN ENTOURAGE, INCLUDING HIS FRIEND AND CORRESPONDENT NOAH BROOKS, LINCOLN WAS IN GOOD SPIRITS AND HAD A GREAT SENSE OF HUMOR. LATER, IN HIS BOOK WASHINGTON IN LINCOLN'S TIME, BROOKS RECOUNTED THE WEEK-LONG BREAK LINCOLN TOOK WITH JOE HOOKER'S ARMY.

Harper’s Weekly published two illustrations of President Lincoln's review of Hooker's army in april 1863. the illustration here depicts General Buford's Division of Cavalry.

Early in April 1863, I accompanied the President, Mrs. Lincoln, and their youngest son, “Tad,” on a visit to the Army of the Potomac - Hooker then being in command, with headquarters on Falmouth Heights, opposite Fredericksburg. Attorney General Bates and an old friend of Mr. Lincoln, Dr. A. G. Henry of Washington Territory were also of the party. The trip had been postponed for several days on account of unfavorable weather, and it began to snow furiously soon after the President’s little steamer, the Carrie Martin, left the Washington navy yard. So thick was the weather and so difficult the navigation that we were forced to anchor for the night in a little cove in the Potomac opposite Indian Head, where we remained until the following morning. I could not help thinking that if the rebels had made a raid on the Potomac at that time, the capture of the chief magistrate of the United States would have been a very simple matter. So far as I could see, there were no guards on board the boat, and no precautions were taken against a surprise. After the rest of the party had retired for the night, the President, Dr. Henry, and I sat up until long after midnight, telling stories and discussing matters, political or military, in the most free and easy way. During the conversation after Dr. Henry had left us, Mr. Lincoln, dropping his voice almost to a confidential whisper, said, “How many of our iron clads do you suppose are at the bottom of Charleston harbor?” This was the first intimation I had had that the long-talked of naval attack on Fort Sumter was to be made that day, and the President, who had been jocular and cheerful during the evening, began despondently to discuss the probabilities of defeat. It was evident that his mind was entirely prepared for the repulse, the news of which soon after reached us. During our subsequent stay at Hooker’s headquarters, which lasted nearly a week, Mr. Lincoln eagerly inquired every day for the rebel newspapers that were brought in through the picket lines, and when these were received, he anxiously hunted through them for information from Charleston. It was not until we returned to Washington, however, that a trustworthy and conclusive account of the failure of the attack was received.A personal friend and confidant of President Lincoln, few people were closer to the president than noah brooks. His dispatches to the Sacramento Daily Union and his 1895 book Washington in Lincoln's Time is essential reading for understanding Lincoln.

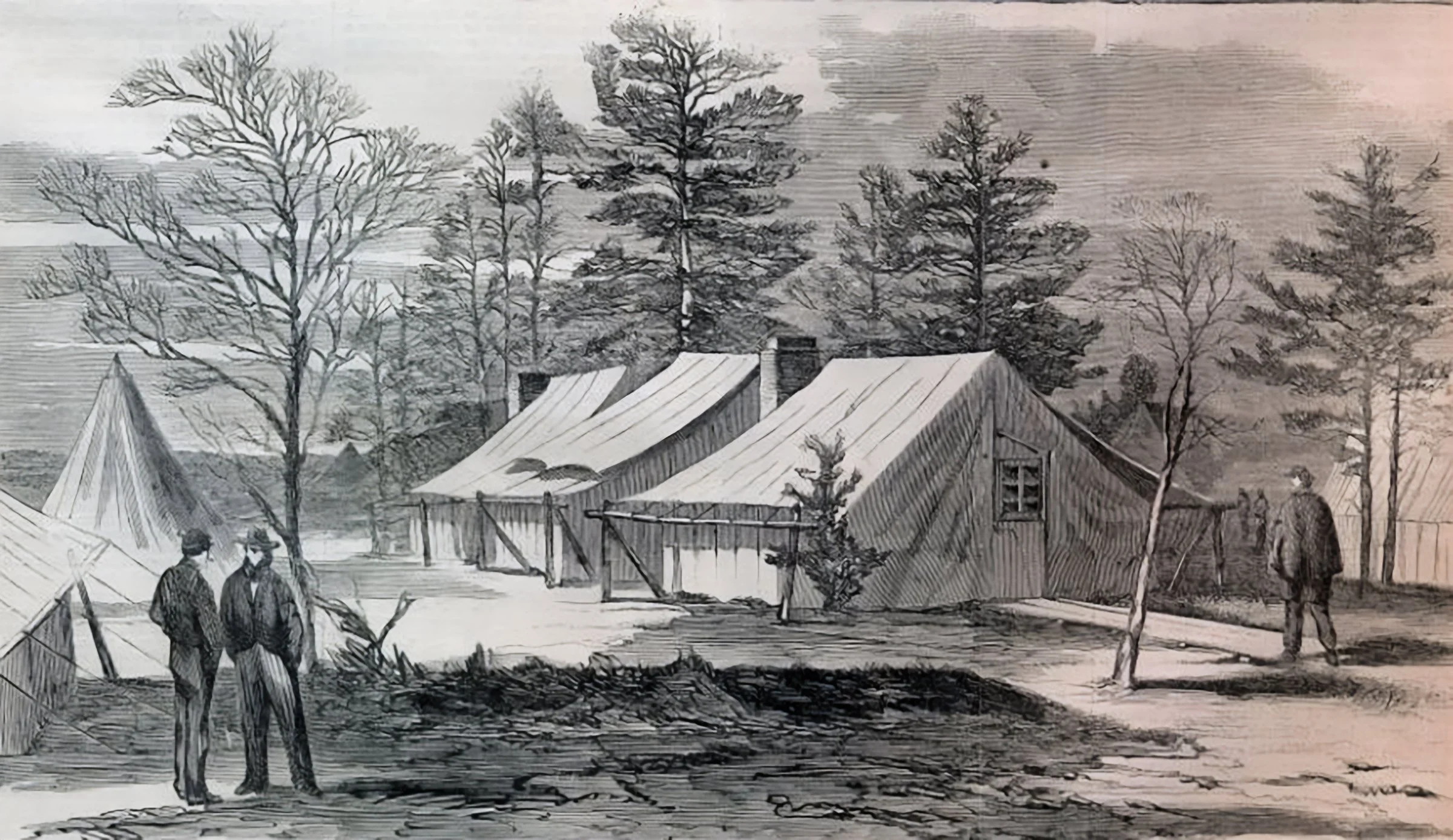

Our landing place, when en route for Falmouth, was at Aquia Creek, which we reached the next morning, the untimely snow still falling. “The Creek,” as it was called, was a village of hastily constructed warehouses, and its waterfront was lined with transports and government steamers; enormous freight trains were continually running from it to the army encamped among the hills of Virginia lying between the Rappahannock and the Potomac. As there were sixty thousand horses and mules to be fed in the army, the single item of daily forage was a considerable factor in the problem of transportation. The President and his party were provided with an ordinary freight car fitted up with rough plank benches and profusely decorated with flags and bunting. A great crowd of army people saluted the President with cheers when he landed from the steamer and with “three times three” when his unpretentious railway carriage rolled away. At Falmouth station, which was about five miles east of the old town, two ambulances and an escort of cavalry received the party, the honors being done by General Daniel Butterfield, who was then General Hooker’s chief of staff.At Hooker’s headquarters, we were provided with three large hospital tents, floored and furnished with camp bedsteads and such rude appliances for nightly occupation as were in reach. During our stay with the army, there were several grand reviews, that of the entire cavalry corps of the Army of the Potomac, on April 6, being the most impressive of the whole series. The cavalry was now, for the first time, massed as one corps instead of being scattered around among the various army corps, as it had been heretofore; it was commanded by General Stoneman. The entire cavalry force was rated at 17,000 men, and Hooker proudly said that it was the biggest army of men and horses ever seen in the world, bigger even than the famous body of cavalry commanded by Marshal Murat.The cavalcade on the way from headquarters to the reviewing field was a brilliant one. The President, wearing a high hat and riding like a veteran, with General Hooker by his side, headed the flying column; next came several major generals, a host of brigadiers, staff officers, and colonels, and lesser functionaries innumerable. The flank of this long train was decorated by the showy uniforms and accouterments of the “Philadelphia Lancers,” who acted as a guard of honor to the President during that visit to the Army of the Potomac. The uneven ground was soft with melting snow, and the mud flew in every direction under the hurrying feet of the cavalcade. On the skirts of this cloud of cavalry rode the President’s little son “Tad,” in charge of a mounted orderly, his gray cloak flying in the gusty wind like the plume of Henry of Navarre. The President and the reviewing party rode past the long lines of cavalry standing at rest, and then the march past began. It was a grand sight to look upon, this immense body of cavalry, with banners waving, music crashing, and horses prancing, as the vast column came winding like a huge serpent over the hills past the reviewing party and then stretching far away out of sight.The President went through the hospital tents of the corps that lay nearest to headquarters and insisted upon stopping and speaking to nearly every man, shaking hands with many of them, asking a question or two here and there, and leaving a kind word as he moved from cot to cot. More than once, as I followed the President through the long lines of weary sufferers, I noticed tears of gladness stealing down their pale faces; for they were made happy by looking into Lincoln’s sympathetic countenance, touching his hand, and hearing his gentle voice; and when we rode away from the camp to Hooker’s headquarters, tremendous cheers rent the air from the soldiers, who stood in groups, eager to see the good President.The headquarters tent of General Joseph Hooker as sketched by Alfred Waud.

The infantry reviews were held on several different days. On April 8 was the review of the Fifth Corps, under Meade; the Second, under Couch; the Third, under Sickles; and the Sixth, under Sedgwick. It was reckoned that these four corps numbered some 60,000 men, and it was a splendid sight to witness their grand martial array as they wound over hills and rolling ground, coming from miles around, their arms shining in the distance, and their bayonets bristling like a forest on the horizon as they marched away. The President expressed himself as delighted with the appearance of the soldiery, and he was much impressed by the parade of the great reserve artillery force, some eighty guns, commanded by Colonel De Russy. One picturesque feature of the review on that day was the appearance of the Zouave regiments, whose dress formed a sharp contrast to the regulation uniform of the other troops. General Hooker, being asked by the President if fancy uniforms were not undesirable on account of the conspicuousness which they gave as targets to the enemy’s fire, said that these uniforms had the effect of inciting a spirit of pride and neatness among the men. It was noticeable that the President merely touched his hat in return salute to the officers but uncovered to the men in the ranks. As they sat in the chilly wind, in the presence of the shot-riddled colors of the army and the gallant men who bore them, he and the group of distinguished officers around him formed a notable historic spectacle. After a few days, the weather grew warm and bright, and although the scanty driblets of news from Charleston that were filtered to us through the rebel lines did not throw much sunshine into the military situation, the President became more cheerful and even jocular. I remarked this one evening as we sat in Hooker’s headquarters after a long and laborious day of reviewing. Lincoln replied: “It is a great relief to get away from Washington and the politicians. But nothing touches the tired spot.”On the 9th, the First Corps, commanded by General Reynolds, was reviewed by the President on a beautiful plain at the north of Potomac Creek, about eight miles from Hooker’s headquarters. We rode thither in an ambulance over a rough corduroy road, and as we passed over some of the more difficult portions of the jolting way, the ambulance driver, who sat well in front, occasionally let fly a volley of suppressed oaths at his wild team of six mules. Finally, Mr. Lincoln, leaning forward, touched the man on the shoulder and said:“Excuse me, my friend, are you an Episcopalian? “The man, greatly startled, looked around and replied:“ No, Mr. President, I am a Methodist.”“Well,” said Lincoln, “I thought you must be an Episcopalian because you swear just like Governor Seward, who is a churchwarden.” The driver swore no more.As we plunged and dashed through the woods, Lincoln called attention to the stumps left by the men who had cut down the trees and, with great discrimination, pointed out where an experienced axman made what he called “good butt,” or where a tyro had left conclusive evidence of being a poor chopper. Lincoln was delighted with the superb and inspiring spectacle of the review that day. A noticeable feature of the doings was the martial music of the corps, and on the following day, the President, who loved military music, was warm in his praise of the performances of the bands of the Eleventh Corps, under General Howard and the Twelfth, under General Slocum. In these two corps, the greater portion of the music was furnished by drums, trumpets, and fifes, and with the most stirring and thrilling effect. In the division commanded by General Schurz was a magnificent array of drums and trumpets, and his men impressed us as the best drilled and most soldierly of all who passed before us during our stay.Noah Brooks describing Joe Hooker three decades later: "The handsomest soldier I ever laid my eyes on." Hooker's overconfidence would prove to be his Achille's heel just weeks after Lincoln's visit.

I recall with sadness the easy confidence and nonchalance which Hooker showed in all his conversations with the President and his little party while we were at his headquarters. The general seemed to regard the whole business of command as if it were a larger sort of picnic. He was then, by all odds, the handsomest soldier I ever laid my eyes upon. I think I see him now: tall, shapely, well dressed, though not natty in appearance; his fair red and white complexion glowing with health, his bright blue eyes sparkling with intelligence and animation, and his auburn hair tossed back upon his well-shaped head. His nose was aquiline, and the expression of his somewhat small mouth was one of much sweetness, though rather irresolute, it seemed to me. He was a gay cavalier, alert and confident, overflowing with animal spirits and as cheery as a boy. One of his most frequent expressions when talking with the President was, “When I get to Richmond,” or “After we have taken Richmond,” etc. The President, noting this, said to me confidentially and with a sigh: “That is the most depressing thing about Hooker. It seems to me that he is over-confident.”One night when Hooker and I were alone in his hut, which was partly canvas and partly logs, with a spacious fireplace and chimney, he stood in his favorite attitude with his back to the fire and, looking quizzically at me, said, “The President tells me that you know all about the letter he wrote to me when he put me in command of this army.” I replied that Mr. Lincoln had read it to me, whereupon Hooker drew the letter from his pocket and said, “Wouldn’t you like to hear it again?” I told him that I should, although I had been so much impressed by its first reading that I believed I could repeat the greater part of it from memory. That letter has now become historic; then, it had not been made public. As Hooker read on, he came to this sentence: “You are ambitious, which, within reasonable bounds, does good rather than harm, but I think during Burnside’s command of the army, you took counsel of your ambition and thwarted him as much as you could, in which you did a great wrong to the country and to a most meritorious and honorable brother officer.”Here Hooker stopped and vehemently said: “The President is mistaken. I never thwarted Burnside in any way, shape, or manner. Burnside was preeminently a man of deportment: he fought the battle of Fredericksburg on his deportment; he was defeated on his deportment, and he took his deportment with him out of the Army of the Potomac, thank God!” Resuming the reading of Lincoln’s letter, Hooker’s tone immediately softened, and he finished it almost with tears in his eyes; and as he folded it and put it back in the breast of his coat, he said, “That is just such a letter as a father might write to his son. It is a beautiful letter, and although I think he was harder on me than I deserved, I will say that I love the man who wrote it.” Then he added, “After I have got to Richmond, I shall give that letter to you to have published.” Poor Hooker, he never got to Richmond; but the letter did eventually find its way into print, and, as an epistle from the commander-in-chief of the army and navy of one of the greatest nations of the world, addressed to the newly appointed general of the magnificent army intended and expected to capture the capital of the Confederacy and to crush the rebellion, it has since become one of the famous documents of the time.President Lincoln's confidential communication to General Joe Hooker upon his appointment as commander of the Army of the Potomac was akin to a fatherly advice, as described by Hooker himself. The letter in its entirety is included here.

A peep into the Confederate lines while we were with the army was highly entertaining. “Tad,” having expressed a consuming desire to see how the “graybacks” looked, we were allowed, under the escort of one of General Hooker’s aides and an orderly, to go down to the picket lines opposite Fredericksburg and to take a look at them. On our side of the river, the country had been pretty well swept by shot and by the axmen, and the general appearance of things was desolate in the extreme. The Phillips House, which was Burnside’s headquarters during the battle of Fredericksburg, had been burned down, and the ruins of that elegant mansion, built in the olden times, added to the sorrowful appearance of the region desolated by war. Here and there stood the bare chimneys of houses destroyed, and across the river, the smoke from the camps of the enemy rose from behind a ridge, and a flag of stars and bars floated over a handsome residence on the heights just above the stone wall where our men were slain by thousands during the dreadful fight of December 1862. The town of Fredericksburg could be thoroughly examined through a field glass, and almost no building in sight from where we stood was without battle scars. The walls of the houses were rent with shot and shell, and loose sheets of tin were fluttering from the steeple of a church that had been in the line of fire. A tall chimney stood solitary by the river’s brink, and on its bare and exposed hearthstone, two rebel pickets were warming themselves, for the air was frosty. One of them wore, with a jaunty swagger, a United States light-blue army overcoat. Noting our appearance, these cheerful sentinels bawled to us that our forces had been “licked” in the recent attack on Fort Sumter, and a rebel officer, hearing the shouting, came down to the riverbank and closely examined our party through a field glass. On the night before our arrival, when Hooker had vainly looked for us, a rebel sentry on the south side of the Rappahannock had asked if “Abe and his wife” had come yet, showing that they knew pretty well what was going on inside the Union lines. The officer inspecting our party, apparently having failed to detect the tall form of President Lincoln, took off his hat, made a sweeping bow, and retired. Friendly exchanges of tobacco, newspapers, and other trifles went on between the lines, and it was difficult to imagine, so peaceful was the scene, that only a few weeks had passed since this was the outer edge of one of the bloodiest battlefields of the war.One of the budgets that came through the lines while we were at Hooker’s headquarters enclosed a photograph of a rebel officer addressed to General Averill, who had been a classmate of the sender. On the back of the picture was the autograph of the officer, with the addendum, “A rebellious rebel.” Mrs. Lincoln, with a strict construction of words and phrases in her mind, said that the inscription ought to be taken as indicating that the officer was a rebel against the rebel government. Mr. Lincoln smiled at this feminine way of putting the case and said that the determined gentleman who had sent his picture to Averill wanted everybody to know that he was not only a rebel but a rebel of rebels, “a double-dyed-in-the-wool sort of rebel,” he added.One day, while we were driving around some of the encampments, we suddenly came upon a disorderly and queer-looking settlement of shanties and little tents scattered over a hillside. As the ambulance drove by the base of the hill as if by magic, the entire population of blacks and yellows swarmed out. It was a camp of colored refugees and a motley throng were the various sizes and shades of color that set up a shrill “Hurrah for Massa Linkum!” as we swept by. Mrs. Lincoln, with a friendly glance at the children, who were almost innumerable, asked the President how many of “those piccaninnies” he supposed were named Abraham Lincoln. Mr. Lincoln said, “Let’s see; this is April 1863. I should say that of all those babies under two years of age, perhaps two-thirds have been named for me.”credits: Washington in Lincoln's Time, by Noah Brooks, 1896. All images are from the Library of Congress unless otherwise indicated. Abraham Lincoln on Horseback and General Burford's Cavalry from Harper's Weekly, May 2, 1863; Hooker's Headquarters, Harper's Weekly, April 18, 1863; Noah Brooks, Wikipedia Commons; Letter to Hooker from Lincoln, Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, edited by Roy P. Basler, et al.