LINCOLN IN RICHMOND

ON APRIL 4, 1865, ABRAHAM LINCOLN VISITED THE RECENTLY ABANDONED CAPITAL OF THE CONFEDERACY WITH HIS SON, TAD. A NAVY CAPTAIN ASSIGNED TO PROTECT THE PRESIDENT PROVIDED A DETAILED ACCOUNT OF THE HISTORIC EVENT.

On April 4, 1865, as Abraham Lincoln and Tad walked from the James River landing to downtown Richmond, the President received a warm and enthusiastic welcome from many black laborers. One of the most poignant images of this moment was Lincoln sitting at the former desk of Jefferson Davis and requesting a glass of water, highlighting the irony of the war's circumstances. ¶ Navy Captain John Sanford Barnes was assigned to protect the president's party during his visit to Richmond, and he provided a detailed account of the historic event. (Harper’s Weekly, February 24, 1866)

The following excerpt is from "With Lincoln from Washington to Richmond in 1865," published in Appleton's, 1907.

Mr. Lincoln remained in Petersburg only an hour or two, when, rejoining the train, we returned to City Point, the President going on board the Malvern for the night. He was in high spirits, seemed not at all fatigued, and said that the end could not be far off. I was on board the Malvern until ten or eleven o’clock that evening. General Weitzel telegraphed confirming the rumor which had reached Grant at Petersburg, that Richmond was being evacuated and that General Lee was in retreat and President Davis had fled. All that evening a lurid glare lit up the sky in the direction of Richmond. Heavy detonations followed each other in rapid succession, which Admiral Porter rightly interpreted as the blowing up of the rebel iron-clads. Mr. Lincoln then made up his mind he would go to Richmond the next day. Mr. Stanton had sent him a telegram, which was delivered that evening, expostulating with him about unnecessary exposure, and drawing a contrast again between the duties of a president and that of a general. This had reference to his proposed visit to Petersburg. Mr. Lincoln replied, in effect, that he had been to Petersburg and was going to Richmond the next day but would take care of himself. Admiral Porter gave orders that evening to the gunboats to clear away the obstructions in the river and to make careful and systematic search for and remove the torpedoes, with which the channel was known to be strewn. This work went on all night. The United States torpedo boat Spuyten Duyvil was employed to blow up the vessels sunk at Deep Bottom, and at eight o’clock in the morning of April 4th the channel was reported as clear and safe. The Admiral sent me word that he was going up to Richmond and would take the President along, and that the Bat could follow. At about 10 A.M., the Malvern leading, followed by the River Queen, with the President, who had returned to her that morning, passed me very near, the Admiral hailing me and telling me to “come on.” Mr. Lincoln was standing on the upper deck of the Queen, and one can imagine his interest in the passing scenes. He waved his hat in answer to my salute as he passed so close that I could see the expression of his face.

A war correspondent for the New York World, George Alfred Townsend ("GATH"), penned the following epilogue to the fall of Richmond:

"A few minutes' walk and we tread the pavements of the capital. there are no beseeching runners; there is no sound of life, but the stillness of a catacomb, only as our footsteps fall dull on the deserted sidewalk, and a funderal troop of echoes bump their elfin heads against the dead walls and close shutters in reply; and this is Richmond. Says a melancholy voice: ‘And this is Richmond.'"

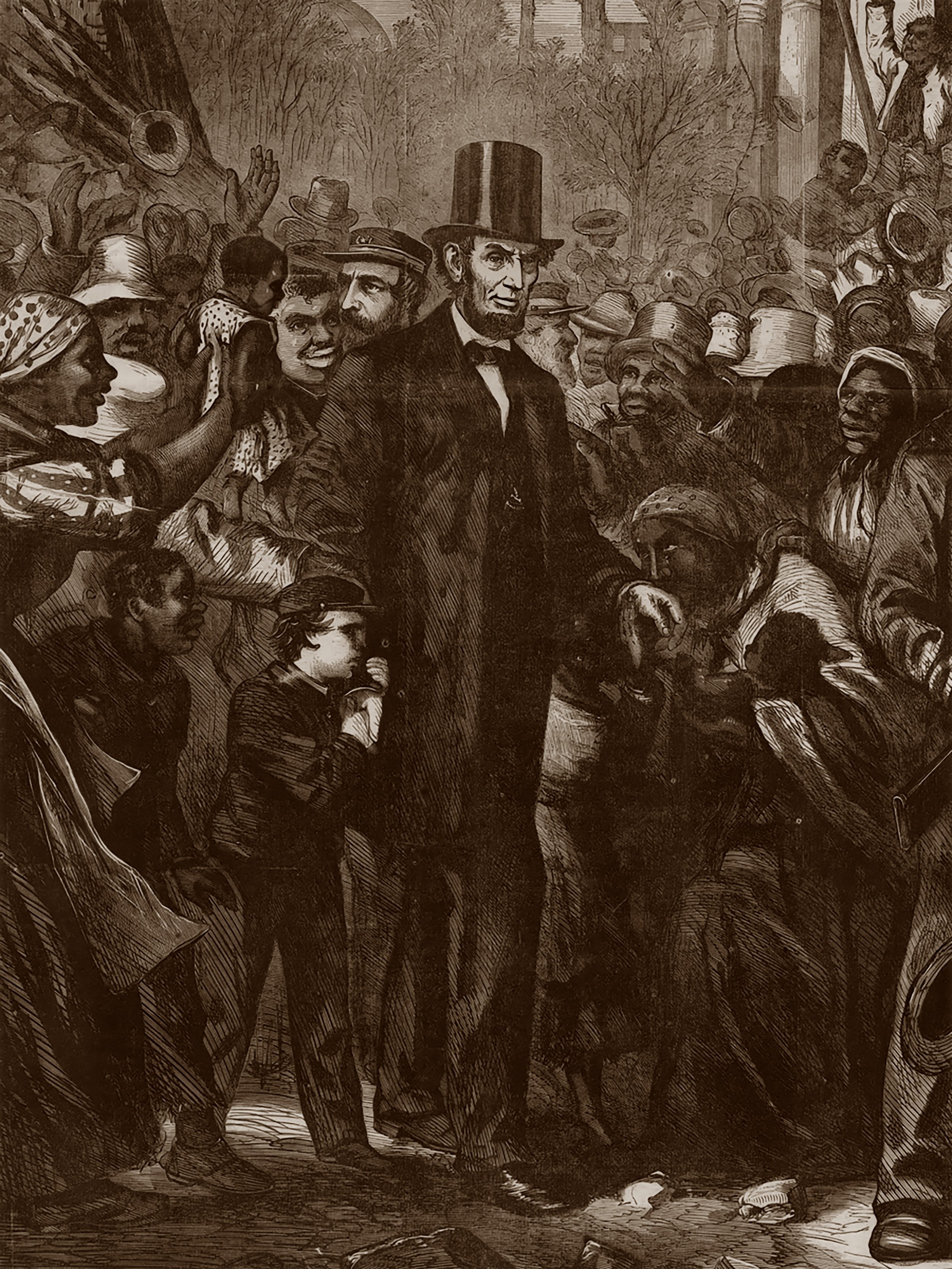

We got our anchor up at once, and followed, passed first through the drawbridge of the pontoon, and then through the gap cleared in the obstructions, which we slightly touched and were delayed for a few moments, during which the Malvern and the Queen, under the guidance of a skillful pilot, got well ahead. The boats from the fleet, still at work searching for torpedoes, had already found many, and had cut the wires of the electric and dragged to the banks many of the floating and submerged mines. Still, I could not avoid a feeling of anxiety for the Malvern and the Queen, as they pushed ahead rapidly, lest some undiscovered mines should be touched and the vessels blown to pieces.A number of vessels had pushed through the obstructions, making quite a display with flags flying from each mast, and finally the Malvern ran hard and fast aground several miles below the city. I came up to her and close to the River Queen and anchored. Richmond appeared to be in flames, dense masses of smoke resting over the city. I found that the Admiral had taken Mr. Lincoln in his barge, and was then pulling under oars toward the city. Manning the gig, I pulled after them as fast as the men could row against a strong current, but Mr. Lincoln was well ahead and the barge finally made a landing on the edge of the town, at a place called Rockett’s, sometime before I reached the spot; and when I got ashore Mr. Lincoln was, with the Admiral and a few sailors, armed with carbines, several hundred yards ahead of me, surrounded by a dense mass of men, women, and children, mostly negroes. Although General Weitzel had been in possession of Richmond since early morning or late the evening before, not a sign of it was in evidence, not a soldier was to be seen, and the street along the riverside in which we were, at first free from people, became densely thronged, and every moment became more and more packed with them. With one of my officers, the surgeon, I pushed my way through the crowd endeavoring to reach the side of the President, whose tall form and high beaver hat towered above the crowd. In vain I struggled to get nearer to him. In some way they had learned that the man in the high hat was President Lincoln, and the constantly increasing crowd, particularly the negroes, became frantic with excitement.Rocketts Landing as it appeared when President Abraham Lincoln stepped ashore from the steamship Malvern, April 1865. (Library of Congress)

I confess that I was much alarmed at the situation and the exposure of the President to assault or even assassination. I did not know of Admiral Porter’s destination, or where the route pursued by him would lead us. He had supposed, as I did, that General Weitzel had full possession of the city, and that, upon landing, communication would at once be made with him, and proper escort provided. Nothing could have been easier than the destruction of the entire party. I cannot say what were the President’s or the Admiral’s reflections, but the situation was very alarming to me. I saw that they were pushed, hustled, and elbowed along without any regard to their persons, while I was packed closely, and simply drifted along in their general direction. This state of things lasted a half hour or more. The day was very warm, and as we progressed the street became thick with dust and smoke from the smoldering ruins about us. At last, when the conditions had become almost unendurable, a cavalryman was found standing at a street corner, and word was sent by him to the nearest post that President Lincoln wished for assistance. He galloped off and in a few minutes a small squadron of mounted men made its appearance. They quickly cleared the street, and joining Mr. Lincoln and the Admiral, we were escorted to General Weitzel’s headquarters, which he had established in the Confederacy White House close to the Capitol grounds. It was a modest and unpretentious building, brown in color, with small windows and doors.

The President entered by the front door that opened into a small square hall with steps leading to the second story. He was then led into the room on the right, which had been Mr. Davis’s reception room and office. It was plainly but comfortably furnished a large desk on one side, a table or two against the walls, a few chairs , and one large leather - covered arm or easy chair . The walls were decorated with prints and photographs, one or two of Confederate ironclads one of the Sumter, that excited my covetousness. Mr. Lincoln walked across the room to the easy chair and sank down in it. He was pale and haggard, and seemed utterly worn out with fatigue and the excitement of the past hour. A few of us were gathered about the door; little was said by anyone. It was a supreme moment - the home of the fleeing President of the Confederacy invaded by his opponents after years of bloody contests for its possession and now occupied by the President of the United States, Abraham Lincoln, seated in the chair almost warm from the pressure of the body of Jefferson Davis! What thoughts were coursing through the mind of this great man no one can tell. He did not live to relate his own impressions; what he said remains fixed in my memory - the first expression of a natural one - “I wonder if I could get a drink of water.” He did not appeal to any particular person for it I can see the tired look out of those kind blue eyes over which the lids half drooped; his voice was gentle and soft. There was no triumph in his gesture or attitude. He lay back in the chair like a tired man whose nerves had carried him beyond his strength. All he wanted was rest and a drink of water.This marble-columned house, built in 1818, served as the executive residence of Jefferson Davis from August 1861 until April 1865. After federal forces occupied Richmond, the building became the headquarters for General Weitzel's XVIII Corps. (Library of Congress)

Very soon, a large squadron of cavalry came clattering to the door. General Weitzel and General Shepley came in, and general conversation ensued. Congratulations were exchanged. In a few minutes, a luncheon was served, procured by the General - a soldier’s luncheon, simple and frugal.Carriages were then sent for, and under military escort Mr. Lincoln was driven to places of interest about the city. After looking with curiosity about the house, I saw from the door a lot of soldiers and people around the Capitol, and walked over to it. It was a scene of indescribable confusion. Confederate bonds of the denomination of $ 1,000 were scattered about on the grass, bundles of public papers and documents littered the floors, chairs and desks were upset, with every evidence of hasty abandonment and subsequent looting. Free access to all parts of the building was seemingly permitted, but at the State Library a sentry had been posted. I returned to Mr. Davis’s house, now General Weitzel’s headquarters, and finally secured a rickety wagon, drove around the town and back to the landing, where I found my boat and returned to the Bat.Mr. Lincoln soon after came down to the Malvern in a tug and remained on the flagship that night. On the following day he had an interview with Judge Campbell, former Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, and one of the most prominent citizens of Richmond, who came with General Weitzel. Conferences took place which have passed into the history of the war. I was told that other late Confederates called also, but I was not present at any of the meetings. With Admiral Porter’s permission, I got under way and returned to City Point early in the forenoon. The Malvern came down later in the day.Mrs. Lincoln had arrived that day also, coming from Washington with a large party, including Mr. Seward, Secretary of State , Senator Sumner, Mr. Colfax, and many others. Mr. Lincoln returned to the River Queen. I saw him but for a moment, when he told me that he would return to Washington within the next two days.Mrs. Lincoln and her party went to Richmond the next day, the 7th, returning early in the afternoon. The President did not accompany them. That day came the news of Sheridan’s victory over Lee’s army and the proposals for surrender. The war was practically over.Notwithstanding the situation at Richmond and the impending surrender of General Lee there were plots to seize the ferry-boat at Havre de Grace, and other predatory expeditions were afoot in the Chesapeake Bay, so that some anxiety was yet felt for Mr. Lincoln’s safety on the River Queen. Admiral Porter, somewhat conscience-stricken at the danger to which he had unintentionally or unexpectedly exposed the President on the trip to Richmond, now became full of concern lest some mishap should occur during Mr. Lincoln’s trip back to Washington, for which he or the Navy might be held responsible. My orders from the department were explicit that I should accompany the River Queen to City Point and thence to the national capital.Built-in Wilmington, Delaware, in 1860 by Harland and Hollingsworth, the USS Malvern transported President Lincoln to Richmond in April 1865. (Wikimedia Commons)

Of possible, he would have had the Queen convoyed by additional vessels and with more ceremony, but the Queen was fast; Mr. Lincoln was in haste to reach Washington, and there was no vessel in the squadron that could begin to keep pace with her except the Bat.Before leaving City Point the Admiral summoned me to the Malvern, and talked over the precautions to be taken during the trip, and for him exhibited great uneasiness and solicitude for the President’s safe conduct. As a result I caused to be domiciled on the Queen two officers, acting ensigns, with a guard of sailors, with minute instructions for guarding the President’s person day and night. The crew of the River Queen were examined and their records taken.We left City Point on the morning of April 8th, the Queen leading under direction of a river pilot, the Bat following closely, pushed to her utmost speed. I remained on the Queen until our arrival at Fortress Monroe, where a brief stop was made for mails and to send and receive telegrams.The President was more than kind in his manner and bearing toward me and so endeared himself to me that the affection I felt for him became veneration. Mrs. Lincoln was indisposed, and I did not meet her. It was clear that her illness gave the President grave concern.After getting the mails, telegrams, and dispatches, also a Chesapeake Bay and Potomac River pilot, I bade the President farewell and returned to the Bat, lying close by, not anchored. Mr. Lincoln was kind enough to thank me for the good care taken of him and made some jocular allusions to the comforts of navy men in war times as we parted. It was the last I saw of him. Probably he never again thought of me; but the memory of his warm handclasp and kindly look remained with me and has never left me.We left Fortress Monroe that afternoon and steamed rapidly up the bay. The Bat’s boilers had a trick of foaming, when changing from salt water to fresh, so that we were hard put to it to keep pace with the Queen, and she slowed down once or twice to enable us to come up to her. After entering the Potomac River, despite our best effort, we fell behind, so that the Queen reached her dock at Washington some hours before us; and on going aboard of her I found that the President had been met by his carriage and had driven at once to the White House. This was on April 10th, the day after General Lee’s formal surrender to General Grant. I reported in person to the Secretary at the Navy Department, saw Mr. Fox for a moment, and was directed verbally to return to Fortress Monroe. After making some slight repairs to the engines at the Navy Yard I started for Hampton Roads on April 11th, stopped at Point Lookout to visit my father, General James Barnes, then in command of the District of St. Mary’s, visited the camp of Confederate prisoners established there, and witnessed their joyful reception of the news of Lee’s surrender and the prospect of the immediate ending of their captivity. The next day I proceeded on my way to Hampton Roads. The weather was thick and stormy and being without a pilot I deemed it prudent to anchor in the dense fog when within twenty-five or thirty miles of the Roads. The fog lifting at last, I went ahead, reaching my anchorage on the 12th, and was informed by Commodore Rockendorf, senior officer, that he had a telegram from Admiral Porter at City Point, directing me to be ready to take him to Washington immediately on his arrival from the former place, and that he would be down the next day. On the 14th he came on the Tristram Shandy, also a converted blockade runner. I called upon him and found that he had made up his mind to continue on to Baltimore in the Shandy. He was delighted to know that the President was safe and sound in the White House. General Grant had left for Washington on the 12th, and the Admiral thought he also ought to be there and said that there was now nothing left for the Navy to do but “clear up the decks”; that he should give up the squadron and seek rest and shore duty. He promised to look out for my interests in the same direction. Getting up anchor, he steamed off swiftly, leaving us to twirl our thumbs and wonder what next.“Mr. Lincoln was kind enough to thank me for the good care taken care of him and made some jocular allusions to the comforts of navy men in war times as we parted. it was the last time i saw him”

On the early morning of April 15th, I was awakened by the orderly saying that the flag- ship had hoisted her colors at half-mast and had made signals for me to come on board at once. It was an unusual hour for such a signal of distress and such a peremptory summons, so that I knew that something grave must have given occasion for it. I immediately thought of Admiral Porter and feared that something had happened to the Tristram Shandy. I dressed in haste and, calling away my gig, was soon on the deck of the flagship Minnesota. Commodore Rockendorf received me at the gangway, his countenance showing the greatest consternation. He made no reply to my anxious inquiry, but taking me by the arm, led me to his cabin, and there placed in my hands this telegram from Mr. Welles, Secretary of the Navy:“President Lincoln was assassinated last night in Ford’s Theater, and is dead."I read it and reread it. It seemed as though the fact could not impress itself upon my mind. For some moments I could not utter a word, while the Commodore walked away in silence. When at last I took in the meaning of those few words, I am not ashamed to say I sat down and gave way to a bitter grief that was heartfelt and sincere.