Life in Log Huts

FROM THE MUNDANE TO THE MOROSE, JOHN BILLINGS’ DAY TO DAY ACCOUNT OF WHAT LIFE WAS LIKE FOR THE CIVIL WAR SOLDIER IS STILL A FASCINATING READ.

The camp of a regiment or battery was supposed to be laid out in regular order as definitely prescribed by Army Regulations. These, I may state in a general way, provided that each company of a regiment should pitch its tents in two files, facing on a street which was at right angles with the color-line of the regiment. This color-line was the assigned place for regimental formation. Then, without going into details, I will add that the company officers’ tents were pitched in rear of their respective companies, and the field officers, in rear of these. Cavalry had something of the same plan, but with one row of tents to a company, while the artillery had three files of tents, one to each section.

All of this is preliminary to saying that while there was in Army Regulations this prescribed plan for laying out camps, yet the soldiers were more distinguished for their breach than their observance of this plan. Army Regulations were adopted for the guidance of the regular standing army; but this same regular army was now only a very small fraction of the Union forces, the largest portion by far-- “the biggest half,” to use a Hibernianism - were volunteers, who could not or would not all be bound by Army Regulations. In the establishing of camps, therefore, there was much of the go-as-you-please order of procedure. It is true that regiments commanded by strict disciplinarians were likely to and did keep pretty close to regulations. Many others approximated this standard, but still there then remained a large residuum who suited themselves, or, rather, perhaps did not attempt to suit anybody unless compelled to by superior authority; so that in entering some camps one might find everything betokening the supervision of a critical military spirit, while others were such a hurly-burly lack of plan that a mere plough-jogger might have been, and perhaps was, the controlling genius of the camp. When troops located in the woods, as they always did for their winter cantonments, this lack of system in the arrangement was likely to be deviated from on account of trees. But to the promised topic of the chapter.

Come with me into one of the log huts. I have already spoken of its walls, its roof, its chimney, its fireplace. The door we are to enter may be cut in the same end with the fireplace. Such was often the case, as there was just about unoccupied space enough for that purpose. But where four or more soldiers located together it was oftener put in the center of one side. In that case the fireplace was in the opposite side as a rule. In entering a door at the end one would usually observe two bunks across the opposite end, one near the ground (or floor, when there was such a luxury, which was rarely), and the other well up towards the top of the walls. I say, usually. It depended upon circumstances. When two men only occupied the hut there was one bunk. Sometimes when four occupied it there was but one, and that one running lengthwise. There are other exceptions which I need not mention; but the average hut contained two bunks.Inside View of a Log Hut

The construction of these bunks was varied in character. Some were built of boards from hardtack boxes; some of the barrel-staves laid crosswise on two poles; some men improvised a spring bed of slender saplings, and padded them with a cushion of hay, oak or pine leaves; others obtained coarse grain sacks from an artillery or cavalry camp, or from some wagon train, and by making a hammock-like arrangement of them thus devised to make repose a little sweeter. At the head of each bunk were the knapsacks or bundles which contained what each soldier boasted of personal effects. These were likely to be under-clothes, socks, thread, needles, buttons, letters, stationery, photographs, etc. The number of such articles was fewer among infantry than among artillerymen, who, on the march, had their effects carried for them on the gun carriages and caissons. But in winter quarters both accumulated a large assortment of conveniences from home, sent on in the boxes which so gladdened the soldier’s heart.

The haversacks, and canteens, and the equipment usually hung on pegs inserted in the logs. The muskets had no regular abiding-place. Some stood them in a corner, some hung them on pegs by the slings.

Domestic conveniences were not entirely wanting in the best ordered of these rude establishments. A hardtack box nailed end upwards against the logs with its cover on leather hinges serving as a door, and having suitable shelves inserted, made a very passable dish-closet; another such box put upside down on legs, did duty as a table — small, but large enough for the family, and useful. Over the fireplace one or more shelves were sometimes put to catch the brie a brac of the hut, and three-or four-legged stools enough were manufactured for the inmates. But such a hut as this one I have been describing was rather high-toned. There were many huts without any of these conveniences.

A soldier’s table-furnishings were his tin dipper, tin plate, knife, fork, and spoon. When he had finished his meal, he did not in many cases stand on ceremony, and his dishes were tossed under the bunk to await the next meal. Or, if he condescended to do a little dish-cleaning, it was not of an aesthetic kind. Sometimes he was satisfied to scrape his plate out with his knife, and let it go at that. Another time he would take a wisp of straw or a handful of leaves from his bunk and wipe it out. When the soft bread was abundant, a piece of that made a convenient and serviceable dishcloth and towel. Now and then a man would pour a little of his hot coffee into his plate to cleanse it. While here and there one, with neither pride, nor shame, nor squeamishness would take his plate out just as he last used it, to get his ration, offering no other remark to the comment of the cook than this, that he guessed the plate was a fit receptacle for the ration. As to the knife and fork, when they got too black to be tolerated — and they had to be of a very sable hue, it should be said — there was no cleansing process so inexpensive, simple, available, and efficient as running them vigorously into the earth a few times.

For lighting these huts the government furnished candles in limited quantities: at first long ones, which had to be cut for distribution; but later they provided short ones. I have said that they were furnished in limited quantities. I will modify that statement. Sometimes they were abundant, sometimes the contrary; but no one could account for a scarcity. It was customary to charge quartermasters with peculation in such cases, and it is true that many of them were rascals, but I think they were sometimes saddled with burdens that did not belong to them. Some men used more light than others. Indeed, some men were constitutionally out of everything. They seemed to have conscientious scruples against keeping rations of any description in stock for the limit of time for which they were drawn.Army Candlesticks

As to candlesticks, the government provided the troops with these by the thousands. They were of steel, and very durable, but were supplied only to the infantry, who had simply to unfix bayonets, stick the points of the same in the ground, and their candlesticks were ready for service. As a fact, the bayonet shank was the candlestick of the rank and file who used that implement. It was always available, and just “filled the bill” in other respects. Potatoes were too valuable to come into very general use for this purpose. Quite often the candle was set up on a box in its own drippings.

Whenever candles failed, slush lamps were brought into use. These I have seen made by filling a sardine box with cookhouse grease and inserting a piece of rag in one corner for a wick. The whole was then suspended from the ridgepole of the hut by a wire. This wire came to camp around bales of hay brought to the horses and mules.

The bunks were the most popular institutions in the huts. Soldiering is at times a lazy life, and bunks were then liberally patronized; for, as is well known, ottomans, lounges, and easy chairs are not a part of a soldier’s outfit. For that reason, the bunks served as a substitute for all these luxuries in the line of furniture.

I will describe in greater detail how they were used. All soldiers were provided with a woollen and a rubber blanket. When they retired, after tattoo roll call, they did not strip to the skin and put on night-dresses as they would at home. They were satisfied, ordinarily, with taking off coat and boots, and perhaps the vest. Some, however, stripped to their flannels, and donning a smoking-cap, would turn in, and pass a very comfortable night. There were a few in each regiment who never took off anything, night or day, unless compelled to; and these turned in at night in full uniform, with all the covering they could muster. I shall speak of this class in another connection.

There was a special advantage in two men bunking together in winter-quarters, for then each got the benefit of the other’s blankets — no mean advantage, either, in much of the weather. It was a common plan with the soldiers to make an under-sheet of the rubber blanket, the lining side up, just as when they camped out on the ground, for it excluded the cold air from below in the one case as it kept out dampness in the other. Moreover, it prevented the escape of animal heat.

I think I have said that the half-shelters were not impervious to a hard rain. But I was about to say that whenever such a storm came on it was often necessary for the occupants of the upper bunk to cover that part of the tent above them with their rubber blankets or ponchos; or, if they did not wish to venture out to adjust such a protection, they would pitch them on the inside. When they did not care to bestir themselves enough to do either, they would compromise by spreading a rubber blanket over themselves, and let the water run off onto the tent floor.(K)nitting Work

At intervals, whose length was governed somewhat by the movements of the army, an inspector of government property put in an appearance to examine into the condition of the belongings of the government in the possession of an organization, and when in his opinion any property was unfit for further service it was declared condemned, and marked with his official brand, I C, meaning, Inspected Condemned. This I C became a byword among the men, who made an amusing application of it on many occasions.

In the daytime, the men lay in their bunks and slept, or read a great deal, or sat on them and wrote their letters. Unless otherwise forbidden, callers felt at liberty to perch on them; but there was such a wide difference in the habits of cleanliness of the soldiers that some proprietors of huts had, as they thought, sufficient reasons why no one else should occupy their berths but themselves, and so, if the three-legged stools or boxes did not furnish seating capacity enough for company, and the regular boarders, too, the r. b. would take to the bunks with a dispatch which betokened a deeper interest than that required of simple etiquette. This remark naturally leads me to say something of the insect life which seemed to have enlisted with the soldiers for “three years or during the war,” and which required and received a large share of attention in quarters, much more, in fact, than during active campaigning. I refer now, especially, to the Pediculus Vestimenti, as the scientific men call him, but whose picture when it is well taken, and somewhat magnified, bears this familiar outline. Old soldiers will recognize the picture if the name is an odd one to them. This was the historic “grayback” which went in and out before Union and Confederate soldiers without ceasing. Like death, it was no respecter of persons. It preyed alike on the just and the unjust. It inserted its bill as confidingly into the body of the major-general as of the lowest private. I once heard the orderly of a company officer relate that he had picked fifty-two graybacks from the shirt of his chief at one sitting. Aristocrat or plebeian it mattered not. Every soldier seemed foreordained to encounter this pest at close quarters. Eternal vigilance was not the price of liberty. That failed the most scrupulously careful veteran in active campaigning. True, the neatest escaped the longest, but sooner or later the time came when it was simply impossible for even them not to let the left hand know what the right hand was doing.“Turning Him Over”

.

The secretiveness which a man suddenly developed when he found himself inhabited for the first time was very entertaining. He would cuddle all knowledge of it as closely as the old Forty-Niners did the hiding place of their bag of gold dust. Perhaps he would find only one of the vermin. This he would secretly murder, keeping all knowledge of it from his tent-mates, while he nourished the hope that it was the Robinson Crusoe of its race cast away on a strange shore with none of its kind at hand to cheer its loneliness. Alas, vain delusion! In ninety-nine cases out of a hundred this solitary pediculus would prove to be the advance guard of generations yet to come, which, ere its capture, had been stealthily engaged in sowing its seed; and in a space of time all too brief, after the first discovery the same soldier would appoint himself an investigating committee of one to sit with closed doors, and hie away to the desired seclusion. There, he would seat himself, taking his garments across his knees in turn, conscientiously doing his (k)nitting work, inspecting every fibre with the scrutiny of a dealer in broadcloths.

The feeling of intense disgust aroused by the first contact with these creepers soon gave way to hardened indifference, as a soldier realized the utter impossibility of keeping free from them, and the privacy with which he carried on his first “skirmishing,” as this “search for happiness” came to be called, was soon abandoned, and the warfare carried on more openly. In fact, it was the mark of a clean soldier to be seen engaged at it, for there was no disguising the fact that everybody needed to do it.

In cool weather “skirmishing” was carried on in quarters, but in warmer weather the men preferred to go outside of camp for this purpose; and the woods usually found near camps were full of them sprinkled about times by the thousands. Now and then a man could be seen just from the quartermaster with an entire new suit on his arm, bent on starting afresh. He would hang the suit on a bush, strip off every piece of the old, and set fire to the same, and then don the new suit of blue. So far well; but he was a lucky man if he did not share his new clothes with other hungry pediculi inside of a week.

“Skirmishing,” however, furnished only slight relief from the oppressive attentions of the grayback, and furthermore took much time. Hot water was the sovereign remedy, for it penetrated every mesh and seam, and cooked the millions yet unborn, which Job himself could not have exterminated by the thumbnail process unaided. So tenacious of life were these creatures that some veterans affirm they have seen them still creeping on garments taken out of boiling water, and that only by putting salt in the water were they sure of accomplishing their destruction. I think there was but one opinion among the soldiers in regard to the graybacks; viz., that the country was being ruined by overproduction. What the Colorado beetle is to the potato crop they were to the soldiers of both armies, and that man has fame and fortune in his hand who, before the next great war in any country, shall have invented an extirpator which shall do for the pediculus what paris-green does for the potato-bug. From all this it can readily be seen why no good soldier wanted his bunk to be regarded as common property.

I may add in passing that no other variety of insect life caused any material annoyance to the soldier. Now and then a wood-tick would insert his head, on the sly, into some part of the human integument; but these were not common or unclean. Boiling Them

I have already related much that the soldier did to pass away time. I will add to that which I have already given two branches of domestic industry that occupied a considerable time in log huts with a few, and less - very much less indeed - with others. I refer to washing and mending. Some of the men were just as particular about changing their underclothing at least once a week as they would be at home, while others would do so only under the severest pressure. It is disgusting to remember, even at this late day, how little care hundreds of the men be-stowed on bodily cleanliness. The story, quite familiar to old soldiers, about the man who was so negligent in this respect that when he finally took a bath he found a number of shirts and socks which he supposed he had lost, arose from the fact of there being a few men in every organization who were most unaccountably regardless of all rules of health, and of whom such a statement would seem, to those that knew the parties, only slightly exaggerated.

How was this washing done? Well, if the troops were camping near a brook, that simplified the matter somewhat; but even then, the clothes must be boiled, and for this purpose there was but one resource--the mess kettles. There is a familiar anecdote related of Daniel Webster: that while he was Secretary of State, the French Minister at Washington asked him whether the United States would recognize the new government of France - I think Louis Napoleon’s. Assuming a very solemn tone and posture, Webster replied: “Why not? The United States has recognized the Bourbons, the French Republic, the Directory, the Council of Five Hundred, the First Consul, the Emperor, Louis XVIII., Charles X., Louis Philippe, the” - “Enough! Enough!” cried the minister, fully satisfied with the extended array of precedents cited. So, in regard to using our mess kettles to boil clothes in, it might be asked “Why not?” Were they not used to boil our meat and potatoes in, to make our bean, pea, and meat soups in, to boil our tea and coffee in, to make our apple and peach sauce in? Why not use them as wash-boilers? Well, “gentle reader,” while it might at first interfere somewhat with your appetite to have your food cooked in the wash-boiler, you would soon get used to it; and so this complex use of the mess kettles soon ceased to affect the appetite, or to shock the sense of propriety of the average soldier as to the eternal fitness of things, for he was often compelled by circumstances to endure much greater improprieties. It would indeed have been a most admirable arrangement in many respects could each man have been provided with an excellent Magee Range with copper-boiler annex and set tubs nearby; but the line had to be drawn somewhere, and so everything in the line of impedimenta was done away with, unless it was absolutely essential to the service. For this reason we could not take along a well-equipped laundry, but must make some articles do double or triple service.Cleaning Up

It may be asked what kind of a figure the men cut as washerwomen. Well, some of them were awkward and imperfect enough at it; but necessity is a capital teacher, and, in this as in many other directions, men did perforce what they would not have attempted at home. It was not necessary, however, for every man to do his own washing, for in most companies there was at least one man who, for a reasonable recompense, was ready to do such work, and he usually found all he could attend to in the time he had off duty. There was no ironing to be done, for “boiled shirts,” as white-bosomed shirts were called, were almost an unknown garment in the army except in hospitals. Flannels were the order of the day. If a man had the courage to face the ridicule of his comrades by wearing a white collar, it was of the paper variety, and white cuffs were unknown in camp.

In the department of mending garments each man did his own work, or left it undone, just as he thought best; but no one hired it done. Every man had a “housewife” or its equivalent, containing the necessary needles, yarn, thimble, etc., furnished him by some mother, sister, sweetheart, or Soldier’s Aid Society, and from this came his materials to mend or darn with.

Now, the average soldier was not so susceptible to the charms and allurements of sock-darning as he should have been; for this reason he always put off the direful day until both heels looked boldly and with hardened visage out the back-door, while his ten toes ranged themselves en echelon in front of their quarters. By such delay or neglect good ventilation and the opportunity of drawing on the socks from either end were secured. The task of once more restricting the toes to quarters was not an easy one, and the processes of arriving at this end were not many in number. Perhaps the speediest and most unique, if not the most artistic, was that of tying a string around the hole. This was a scheme for cutting the Gordian knot of darning, which a few modern Alexanders put into execution. But I never heard any of them commend its comforts after the job was done.

Then, there were other men who, having arranged a checkerboard of stitches over the holes, as they had seen their mothers do, had not the time or patience to fill in the squares, and the inevitable consequence was that both heels and toes would look through the bars only a few hours before breaking jail again. But there were a few of the boys who were kept furnished with home-made socks, knit, perhaps, by their good old grandmas, who seemed to inherit the patience of the grandams themselves; for, whenever there was mending or darning to be done, they would sit by the hour, and do the work as neatly and conscientiously as anyone could desire. I am not wide of the facts when I say that the heels of the socks darned by these men remained firm when the rest of the fabric was well spent.

There was little attempt made to repair the socks drawn from the government supplies, for they were generally of the shoddiest description, and not worth it. In symmetry, they were like an elbow of stovepipe; nor did the likeness end here, for, while the stovepipe is open at both ends, so were the socks within forty-eight hours after putting them on.A Housewife

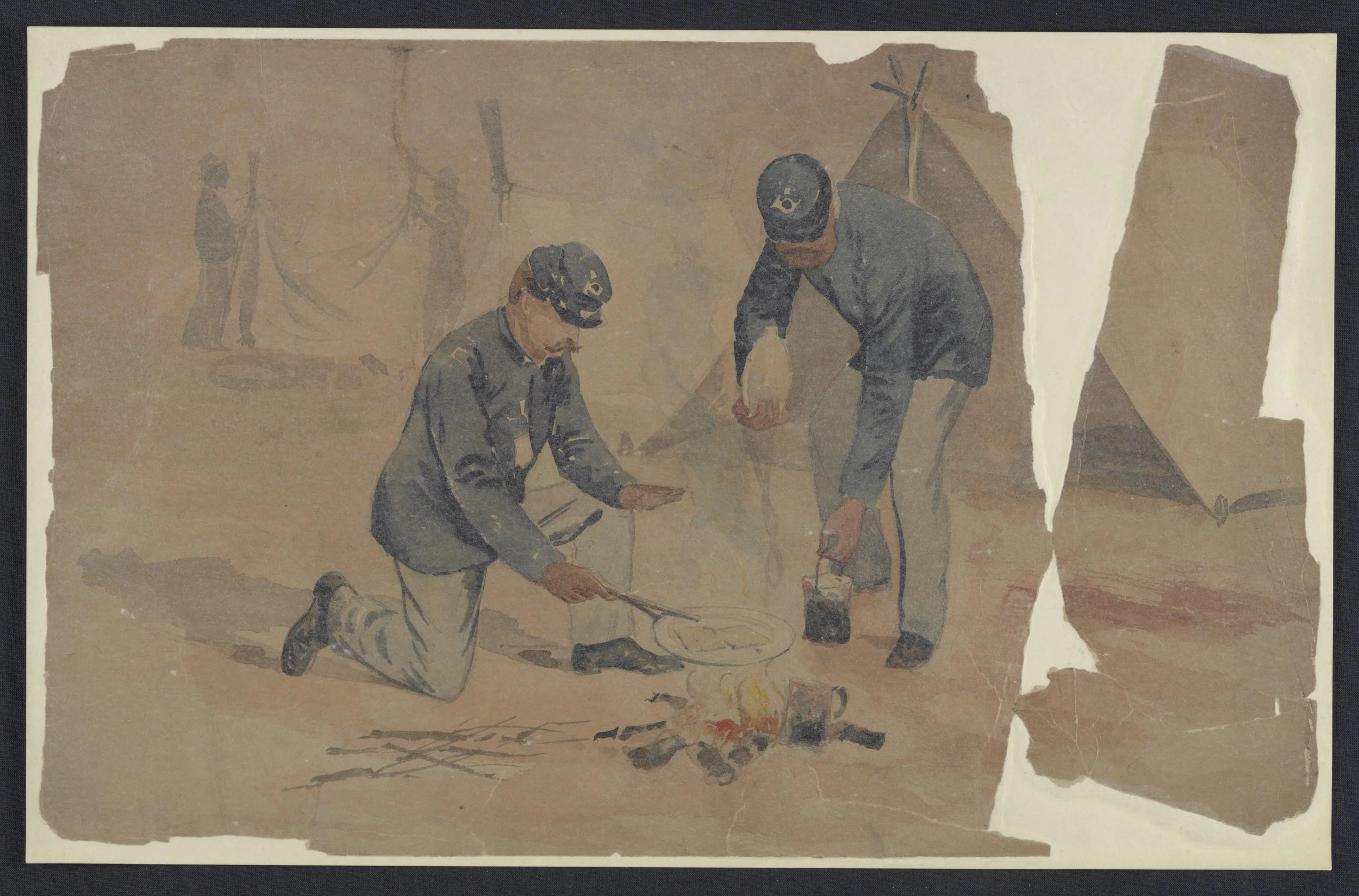

Cooking was also an industry which occupied more or less of the time of individuals; but when the army was in settled camp company cooks usually took charge of the rations. Sometimes, where companies preferred it, the rations were served out to them in the raw state; but there was no invariable rule in this matter. I think the soldiers, as a whole, preferred to receive their coffee and sugar raw, for rough experience in campaigning soon made each man an expert in the preparation of this beverage. Moreover, he could make a more palatable cup for himself than the cooks made for him; for too often their handiwork betrayed some of the other uses of the mess kettles to which I have made reference. Then, again, some men liked their coffee strong, others weak; some liked it sweet, others wished little or no sweetening; and this latter class could and did save their sugar for other purposes. I shall give other particulars about this when I take up the subject of Army Rations.

It occurs to me to mention in this connection a circumstance which may seem somewhat strange to many, and that is that some parts of the army burned hundreds of cords of green pinewood while lying in winter quarters. It was very often their only resource for heat and warmth. People at the North would as soon think of attempting to burn water as green pine. But the explanation of the paradox is this — the pine of southern latitudes has more pitch in it than that of northern latitudes. Then, the heartwood of all pines is comparatively dry. It seemed especially so South. The heartwood was used to kindle with, and the pitchy sapwood placed on top, and by the time the heartwood had burned the sappy portion had also seasoned enough to blaze and make a good fire. These pines had the advantage over the hard woods of being more easily worked up — an advantage which the average soldier appreciated.The Camp Barber

Nearly every organization had its barber in established camp. True, many men never used the razor in the service, but allowed a shrubby, straggling growth of hair and beard to grow, as if to conceal them from the enemy in time of battle. Many more carried their own kit of tools and shaved themselves, frequently shedding innocent blood in the service of their country while undergoing the operation. But there was yet a large number left who, whether from lack of skill in the use or care of the razor, or from want of inclination, preferred to patronize the camp barber. This personage plied his vocation inside the tent in cold or stormy weather, but at other times took his post in rear of the tent, where lie had improvised a chair for the comfort (?) of his victims. This chair was a product of home manufacture. Its framework was four stakes driven into the ground, two long ones for the back legs, and two shorter ones for the front. On this foundation a superstructure was raised which made a passable barber’s chair. But not all the professors who presided at these chairs were finished tonsors, and the back of a soldier’s head whose hair had been “shingled” by one of them was likely to show each course of the shingles with painful distinctness. The razors, too, were of the most barbarous sort, like the “trust razor” of the old song with which the Irishman got his “Love o’ God Shave.”

One other occupation of a few men in every camp, which I must not overlook, was that of studying the tactics. Some were doing it, perhaps, under the instructions of superior officers; some because of an ambition to deserve promotion. Some were looking to passing a competitive examination with a view of obtaining a furlough; and so these men, from various motives, were “booking” themselves. But the great mass of the rank and file had too much to do with the practice of war to take much interest in working out its theory, and freely gave themselves up, when off duty, to every available variety of physical or mental recreation, doing their uttermost to pass away the time rapidly; and even those troops having nearly three years to serve would exclaim, with a cheerfulness more feigned than real, as each day dragged to its close, "It's only two years and a but." Source of text and all images: Billings, John D. Hardtack and Coffee: The Unwritten Story of Army Life (1888)