“This is no Place for a Civilian”: The Adventures of “GATH” During the Civil War

George Alfred Townsend was a special war correspondent for the Philadelphia Press and New York Herald during the Civil War. He followed McClellan’s Army of the Potomac and Pope’s Army of Virginia in the spring and summer of 1862, filing dozens of dispatches to his editors. Finally, after suffering from the effects of ‘swamp fever,’ he took a two-year break in Europe, where he lectured about his experiences. Townsend returned to the war front in 1865 and - after taking the pen name of “GATH” - was the first correspondent to describe the war’s climax at Five Forks. He released his memoir in 1866, detailing his personal experiences and recollections of the Civil War and those dramatic days.

We provide the following sketch of some fascinating scenes described in Campaigns of a Non-Combatant. Townsend chronicles extraordinary events during extraordinary times - the revised issue and additional images and annotations bring new life to the narrative.

G.A. Townsend (l), Mark Twain (c) and Buffalo newsman David Gray (r)

“Our Washington Superintendent sent me a beast, and in complient to what the animal might have been, called the same a horse. I wish to protest, in this record, against any such misnomer.””

Beginnings

Six years after the end of the Civil War, three American journalists sat in Mathew Brady’s Washington, D.C. studio for a group portrait. In the center sat Samuel Clemens, otherwise known as Mark Twain. To his right sat George Alfred Townsend, who like Clemens, was more well known for a pen name: “Gath.” Twain’s literary career had yet to peak; Townsend was more well-known for his notoriety as a correspondent in the late war. While working for the New York Herald, Townsend’s ten-column account of the Army of the Potomac’s retreat to the James River reached the press on July 4, 1862, after Townsend’s dramatic escape from Harrison’s Landing during the Battle of Malvern Hill. Later, in April 1865, working for the New York World, Townsend got the scoop on the victory at Five Forks, which virtually ended Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. A national reputation was earned when in May 1865, he reported on the pursuit and capture of John Wilkes Booth following the assassination of the president.

George Townsend’s success with the pen is a testament to the quality of education he received despite his father’s modest income as a traveling Methodist preacher. His education began around 1849/50 in Chestertown, Maryland, when he was eight or nine. He received an early education at the highly esteemed Washington College in Chestertown, Maryland, which, at the time, accepted students of all ages, including young children and older teens. Later, in 1851, after the family moved to Newark, Delaware, George Alfred enrolled at the Newark Academy, another school that offered instruction for pre-teen boys. In 1853, the family relocated to the urban environment of Philadelphia, where the young man was placed in the Fox Chase School. George Alfred enrolled in Philadelphia’s Central High School in 1856. The school was highly regarded and granted a Bachelor of Arts degree after four years of learning, putting it on par with many colleges.

Townsend’s social awareness and his disdain for the institution of slavery were aroused by the political happenings in the late 1850s. He became aware of the enslavement of others by reading his father’s copy of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. In a later comment, he credited Harriet Beecher Stowe’s work for inspiring him to pursue a literary career. His writing skills improved, and he became involved with Central High’s student newspaper. One of his articles, “The Colored People of this City,” called for equal opportunities for the city’s free African American population and was published in local newspapers. After graduating in 1860, the young man, seeking a literary life, took a job at the Philadelphia Inquirer at six dollars a week.

In the early months of 1861, Townsend’s career prospects improved after Abraham Lincoln was elected president. The Philadelphia Press hired him from the Inquirer, and he was soon promoted to city editor and dramatic editor, where he would meet many of the up-and-coming actors of the nation, including John Wilkes Booth. The outbreak of the Civil War gave Townsend the chance of a lifetime as a special war correspondent covering war events for The Press. In the spring of 1862, he left behind his city beat in Philadelphia and, after a brief interview with Secretary of War Stanton and assigned a disagreeable horse more likened to “a beast,” he crossed the Chain Bridge and began writing dispatches on the sounds and sights of the American conflict.

During the early stages of the war, correspondents were encouraged to reveal their identities. In March 1862, in his first dispatch from Hunter’s Mill, Townsend identified himself as “G.A.T.” and was assigned to shadow General McCall’s Pennsylvania Reserves. His tenure at the Press was brief. He soon drew the ire of the censors at the War Department after divulging too many details about the Pennsylvania Reserve’s covert midnight march to Annapolis on March 17, 1862, and his Philadelphia handlers removed him from his assignment.The Peninsula

The New York press was eager for active correspondents, and the young writer’s talents and abilities were recognized. In May 1862, Townsend returned again to the front, but this time as a correspondent for the New York Herald. Assigned to “Baldy” Smith’s division of the 4th Corps, Army of the Potomac, Townsend was transported to the Peninsula aboard the Adelaide, where he would meet a string of odd characters all part of the tapestry of the Civil War. An embalmer “with his ghostly implements” desiring to develop his art, a Baltimore mother anxious to locate the remains of a Confederate son, and a German immigrant quartered in Townsend’s cabin bent on singing foreign ballads when the sounds of exuberant Zouaves broke out the "Start Spangled Banner" chorus. A view of White House Landing on the Pamunkey River

Exiting the ship at Old Point, the passengers were obligated to pledge the oath of allegiance; the bar at the Hygeia House, an ancient watering hole, “was beset with thirsty and idle people, who swore instinctively and drank raw spirits passionately.” A pass was issued allowing passage by steamer up the York to White House on the Pamunkey River, the massive supply depot of the building federal presence. After a visit to Yorktown and a night aboard a barge, Townsend reached White House the evening of May 17th where he quickly penned a dispatch after overhearing a description of a gunboat excursion up the Pamunkey River.

The cast of characters that Townsend encounters are as diverse as the region he and the army are entering. We find a local native American, Aunt Mag, smelling strongly of “fire water,” and the remaining lot of mixed Indians and African-Americans on an island in the Pamunkey known as Indiantown Island who, for the cost of a dime, would read coffee grinds to predict if Richmond would fall within the week; the elderly, toothless enslaved woman, aged beyond her years from fieldwork, selling buttermilk and corncakes; the wife of a Confederate officer, who on the request for a meal and bread, drank a toast to an early peace. “I almost fell in love with her,” Townsend recalls, “though she might have been a younger playmate of my mothers.”A self-confident pose of Townsend

Wherever Townsend went, he seemed to cross swords with army officials. Once, while accompanying a scouting raid to Hannover Court House, he got lucky and obtained some newspapers with valuable intelligence from Richmond. Ambitious to please his New York editor, Townsend rushed back to the White House depot alone, on a broken down horse, hoping to avoid Yankee picket lines. Arriving early enough to catch his agent at the docks of White House Landing to deliver the newspapers, the provost marshal was waiting for him on the docks: “General McClellan wants those newspapers you obtained at Hannover

yesterday!” Placed under arrest, Townsend was facing serious charges. The father-in-law of General McClellan, General Randolph Marcy, took pity on the young correspondent and soon released him after spending one night in custody.“I heartily wished for the unlucky papers at the bottom of the sea. To gratify an adventurous whim, and obtain a day’s popularity in New York, I had exposed my life, crippled my nag, and was now to be disgraced and punished. What might or might not befall me, I gloomily debated. The least penalty would be expulsion from the army; but imprisonment till the close of the war was a favorite amusement with the War Office. How my newspaper connection would be embarrassed was a more grievous inquiry. It stung me to think that I had blundered twice on the very threshold of my career.””

The Retreat

Most of Townsend’s dispatches before the Seven Day’s Battle were focused on the area north of the Chickahominy River, where he would travel the environs around the vast supply depot of the White House; however, at the beginning of Lee’s offensive on June 25, 1862, Townsend was sick with swamp fever south of the Chickahominy. Fortunately, in classic literary style, he quickly recovered, and recrossed the river at the Grapevine Bridge, where he witnessed “an immense throng of panic-stricken people surging down the slippery bridge.” It was the retreat of the Army of the Potomac where squads, companies and regiments, some in a panic and others not, were making haste for the James River. “I have seen nothing that conveys an adequate idea of the number of cowards and idlers that stroll off," Townsend recalls.

But what of him? Could Townsend stand fire as the bullets whizzed and shells shrieked? “The question at once occurred to

me: Can I stand fire?” he wondered aloud. “Having for some months penned daily paragraphs relative to death, courage,

and victory, I was surprised to find that those words were now unusually significant.” Townsend moved forward about a

mile beyond the bridge to General Porter’s refashioned position on a ridge around “Boatswain’s swamp.” It was June 27, 1862, and Townsend witnessed Lee’s largest attack of the war and the final assault of the Battle of Gaine’s Mill. The correspondent, reciting the simple nursery prayer - “now I lay me down to sleep” - passed the test of combat: “I sat like one dumb, with my soul in my eyes and my ears stunned, watching the terrible column of Confederates.”A Harper’s Weekly engraving of the Battle of Gaine’s Mill, June 27, 1862

With the collapse of the final defenses north of the creek, Townsend along with the rest of the army, took for a hasty retreat to the other side of the Chickahominy. Denied passage to the other side by a martinet colonel, Townsend’s bravado is

set aside:

“Colonel,” I called to the officer in command as the line of bayonets edged me in, “may I pass out? I am a civilian!”

“No!” said the Colonel, wrathfully. “This is no place for a civilian.”

“That’s why I want to get away.”

“Pass out!”

After arriving safely at Harrison’s Landing, Townsend sought safety on a hospital transport to the capital. He arrived in New York on July 3, 1862, and gained attention after writing a ten-column article about the peninsula fiasco and McClellan’s retreat to the James River. The Herald’s headline on July 4th was the first confirmation of the reversal of fortune on the Virginia Peninsula, causing concern among many northern supporters of the war.Cedar Creek

In mid-July 1862, Townsend resumed his duty as a correspondent and joined John Pope’s Army of Virginia. The army was stationed along the Rappahannock River in an attempt to capture Richmond through a land attack. Townsend reported on the battle that occurred on August 9, 1862, and witnessed the fierce fighting.

Departing Alexandria on July 13th, Townsend embarked on the Orange and Alexandria rail where the passengers “were rollicking and well-disposed, and black bottles circulated freely...the beverage offered was intolerably bad.” Always in mind of the fairer sex, Townsend is again smitten with a woman searching for her missing husband: “A pretty woman in wartime is not to be sneezed at.” The neutral town of Warrenton, which experienced being visited one day by Confederates and the next day by Federals, was rife with its own unique set of characters. We find the mayor of the city, operating part-time as a horse trader

and wagon builder, unwilling to deal in Virginia or Confederate money, preferring instead “Father Chase’s greenbacks”; a high-strung hotel owner flush with paper money from two republics, and the local female society of Warrenton “ardent partisans,

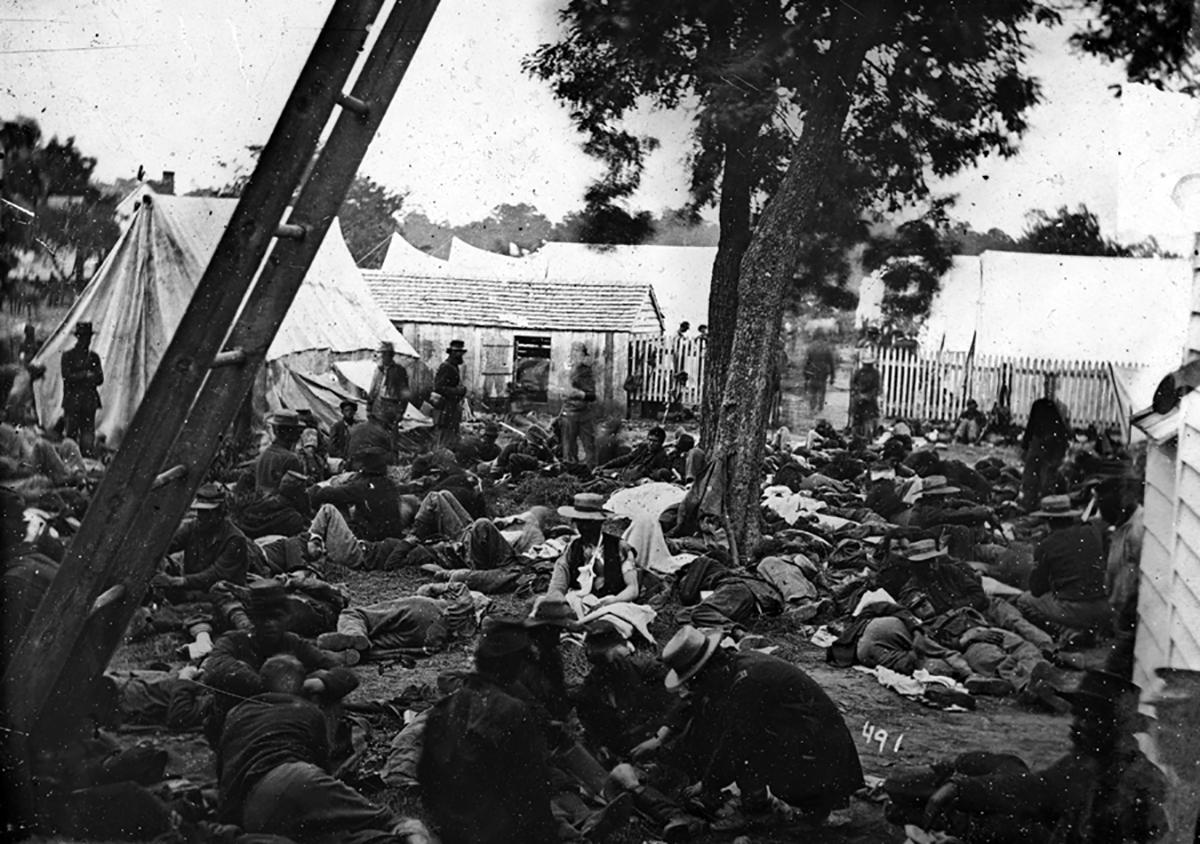

but also very pretty; and treason, heightened their beauty.”The temporary field hospital at Savage Station

“When I returned to Savage’s, where McClellan’s headquarters had temporarily been pitched, I found the last of the wagons creaking across the track and filing slowly southward. The wounded lay in the outhouses, in the trains of cars, beside the hedge, and in shade of the trees about the dwelling.””

The battle itself was a surprise to the correspondent who, while relaxing in the village of Culpepper, heard the sound of musket fire, “I heard the signal that I knew so well—a volley of musketry. Full of all the old impulses, I climbed into the saddle

and spurred my horse towards the battlefield.” Townsend kept his distance this time, “observing the spurts of white cannon smoke far up the side of the mountain.” While collecting the names of the dead and wounded, Townsend was in range of Confederate artillery, one shell “so perfectly in range that I held my breath, and felt my heart grow cold, came toward and passed me, and, with a toss of his head, the nag flung up the rail as if it had been a feather.”

Townsend witnessed one of the oddest encounters between Confederate and Union officers of the war. Following

the battle, a temporary armistice to bury the dead and recover the wounded was negotiated. Townsend recalls the Confederate cavalry officer J.E.B. Stuart confronted him as he sketched the battlefield.

“Are you making a sketch of our position?” General Stuart asked Townsend.

“Not for any military purpose.”

“For what?”

“For a newspaper engraving.”

"Umph!” Stuart replied.

During the brief battlefield truce, Towsend recalled the strange scene of General Stuart, the storied Confederate cavalry leader, telling him about the threads of his uniform and later entertaining his old West Point acquaintances with tales of his exploits riding around the Federal army: “That performance gave me a Major-Generalcy, and my saddle cloth there, was sent from Baltimore as a reward, by a lady whom I never knew!”Five Forks

During the late summer of 1862, Townsend abandoned his anonymous life as a correspondent (by the summer of 1862, special war correspondents were not identified by name) and began a lecture tour in England instead. He entertained his European audiences with stories of his correspondent experiences and contributed articles to the British press. In the spring of 1865, Townsend accepted an offer from the New York World to return to the field and cover the war’s final months. He

was again the first to offer his paper one of the war’s greatest scoops: The Battle of Five Forks. This significant Union victory was the final blow to the Confederacy, and Townsend’s description of the Civil War’s last major battle made him an instant

success. His subsequent dispatches detailing the assassination of President Lincoln and the pursuit of John Wilkes Booth brought him even more fame. By the end of the war, Townsend was one of the most famous newspaper correspondents in

the country.“The music of the battlefield, I have often thought, should be introduced in opera. Not the drum, the bugle, or the

fife, though these are thrilling, after their fashion; but the music of modern ordnance and projectile, the beautiful

whistle of the minnie-ball, the howl of shell that makes unearthly havoc with the air, the whiz-z-z of solid shot, the chirp of bullets, the scream of grape and canister, the yell of immense conical cylinders, that fall like red hot

stoves and spout burning coals.”

“Hancock was one of the handsomest officers in the army”

On Generals

Being a war correspondent for prominent New York newspapers, Townsend had the opportunity to view many commanders

of the Union army, and his unique descriptions contained in the narrative bear repeating.GEORGE B. MCCLELLAN: “While I was standing close by the bridge, General McClellan and staff rode through the swamp and attempted to make the passage. The “young Napoleon” urged his horse upon the floating timber and at once sank over neck and saddle. His staff dashed after him, floundering in the same way, and when they had splashed and shouted till I believed them all drowned, they turned and came to shore, dripping and discomfited. There was another Napoleon, who, I am informed, slid down the Alps into Italy; the present descendant did not slide so far, and he shook himself in the manner of a dog. I remarked with some surprise that he was growing obese, whereas the active labors of the campaign had reduced the dimensions of most of the Generals.”WINFIELD S. HANCOCK: “Hancock was one of the handsomest officers in the army; he had served in the Mexican War and was subsequently a captain in the Quartermaster’s department. But the Rebellion placed stars in many shoulder-bars, and few were more worthily designated than this young Pennsylvanian.” GEORGE GORDON MEADE: “Lithe, spectacled, sanguine...”JOSHUA L. CHAMBERLAIN: “Chamberlain is a young and anxious officer, who resigned the professorship of modern languages in Bowdoin College to embrace a soldier’s career. He had been wounded the day before but was zealous to try

death again."JOE HOOKER: “Hooker was a New Englander, reputed to be the handsomest man in the army. He fought bravely in the Mexican War and retired to San Francisco afterward, where he passed a Bohemian existence at the Union Club House. He

disliked McClellan, was beloved by his men, and was generally known as “Old Joe.” He has been one of the most successful Federal leaders and seems to hold a charmed life. In all probability, he will become commander-in-chief of one of the

grand armies.”PHIL SHERIDAN: “The personnel of the man, not less than his renown, all elected people. A very Punch of soldiers, a sort of Rip Van Winkle in regimentals, it astonished folks, that with so jolly and grotesque a guise, he held within him energies like lightning, the bolts of which had splintered the fairest parts of the border. Sheridan must take rank as one of the finest military men of our century.”credits: Campaigns of a Non-Combatant: The Memoir of a Civil War Correspondent, by George Alfred Townsend, edited by Jeffrey R. Biggs, Hardtack Books, 2024All images are from the Library of Congress unless otherwise indicated.