An Abolitionist at Bull Run

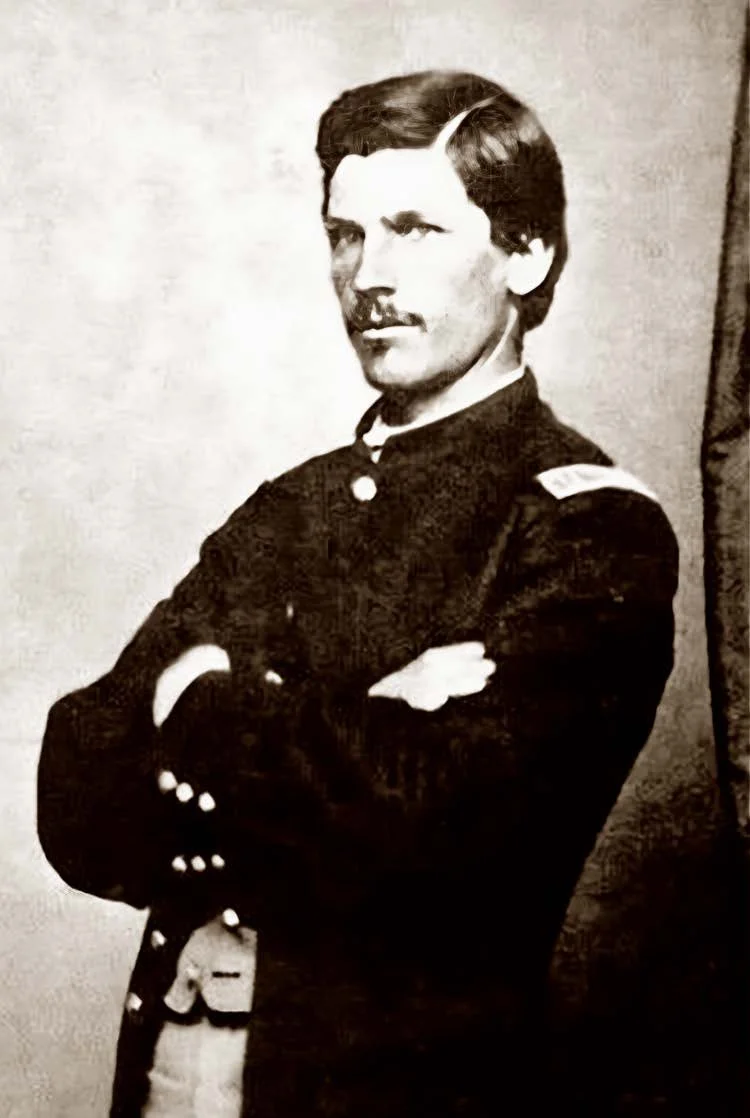

Robert Beecham, 2nd Wisconsin, a courageous twenty-three-year-old from the Midwest, driven by the anti-slavery movement, stands tall with a musket at Bull Run.

The following excerpt of Robert Beecham's memoir appeared in the National Tribune, a popular newspaper followed by veterans, in the August 14, 1902 edition.

In 2007, Rowman and Littlefield published the serialized memoir in full in As if It Were glory: Robert Beecham's Civil war from the Iron Brigade to the Black Regiments, edited by Michael E. Stevens.

I enlisted on May 10th, 1861, in company H, Second Wisconsin. The Second Wisconsin was a three-year regiment, and one of the first mustered into the service of the United States in the war of the rebellion.

From the date of my enlistment until sometime in June we put in the time learning the art of war, hoping all the time that we would not be called upon to practice the art to any great extent. On June 11th, 1861, we were mustered into the United States service, and nine days later, we started for Washington, DC. And that time we enjoyed, to some extent, the pomp of war.

The country through which we passed was full of enthusiasm and the people seemed to wave us on, as if it were glory and not years of bitter war that awaited us. We stopped one day at Harrisburg PA where we received our arms - old Harpers Ferry, smoothbore muskets - which we loaded afterward in the day of battle, with one ball and three buckshot to each piece, with powder sufficient behind ball and buckshot to drive them out of the gun barrel at the same time nearly knocked the life out of the man who stood behind the gun. When we marched through Baltimore, we loaded our pieces and fixed bayonets, as a precautionary measure. In those days Baltimore was a hotbed of treason, and on that march through the city the people delighted our ears with cheers for Jeff Davis; but they carefully refrained from the use of brickbats and stones, so we had no occasion to use our muskets; but the demonstration did not auger an early peace, by any means.We arrived in Washington all safe and sound, and the latter part of June, and then camped for several days in the outskirts of the national capital, which at that time, was nothing more or less than a great, overgrown village. This model 1842 Harpers Ferry percussion musket was manufactured with a smoothbore barrel similar to the one carried by Beecham at the First Battle of Bull Run, July 21, 1861. The model carried "buck and ball" which was a .69 round ball with three rounds of buckshot (National Museum of American History)

On July 2nd our regiment crossed the Potomac River by the way of Long Bridge, into the state of Virginia. We were there brigaded with the 69th, 79th and if any memory serves me, the 13th New York. The 69th was a famous Irish regiment, commanded by Colonel (afterward General) Corcoran, and carried the green flag of the Emerald Isle beside the stars and stripes, the 79th was Cameron’s Scotch regiment, and displayed the thistle of Scotia with the American flag, the same being borne aloft by two brawny, bare legged Scotchman. The other regiment, which was only a common, everyday Yankee regiment like my own - only mine was from the West - had nothing particular about it to fix it in my memory, so I am not certain as to its number, but do remember that it was a New York regiment.

General William Tecumseh Sherman was honored with the command of this brigade of four regiments of volunteers, that this is Sherman’s first important command, he was just as proud of his four superb regiments as an old hen could possibly be with four broods of chickens. Sherman’s brigade was assigned to General Tyler’s division, and further than that we knew but little about the organization of the army. Of course, we knew that General Scott was the general-in-chief, or in supreme command, with headquarters in Washington, while General McDowell commanded the army in the field; that Sherman’s brigade was part of Tyler’s division, and that there were other divisions in McDowell’s army; but we had very little knowledge of the situation, and I presume no army ever went into the field and into battle more completely unqualified to perform intelligently the duties of soldiers and officers. There was but little if any time to drill or study the art of war, for the Confederacy had taken the initiative and confronted us with an army better prepared for a campaign than we were, and that army actually threatened the capital; so we were obliged to put in our time building fortifications and preparing defenses. All that portion of Virginia opposite Washington seemed covered with woods, and the labor required in felling the thousands of acres of trees, that might be used in sheltering and advancing army of the enemy, was great. We participated in one or two brigade drills, or more properly speaking, brigade parades, during the early days of July, while we occupied this position, but the bulk of our time was taken up with hard work in making the position of Washington more secure, until the advance of McDowell’s army began. William Techumseh Sherman as he appeared in May 1865 with a black ribon of mourning noting the assasination of Abraham Lincoln. President Lincoln promoted Sherman to Brigadier General of Volunteers after the first battle of Bull Run and assigned him to duty in the West.

About the middle of July the Bull Run campaign opened. The Second Wisconsin and two or three others were three-year regiments, there were also a few two year troops, but the bulk of their army was composed of three month’s men, whose terms of enlistment would expire within the next 30 days, or the middle of August. Therefore, if McDowell’s army was to capture Richmond and end the rebellion, it was necessary for it to make a forward movement without further delay, while we had soldiers to do the fighting, a fight should become necessary. So, the military authorities seem to reason, and the army moved out on its first great campaign. Sherman's brigade was encamped along the Warrenton Pike - the main thoroughfare leading to Centreville and Manassas - about a mile west of Fort Corcoran. We were supplied with good, comfortable wall tents, but when we started on that campaign, we left our encampment in charge of a Lieutenant and, probably 100 sick and convalescent soldiers. As we had no such thing as shelter tents in those days, each soldier rolled a woolen inside of a rubber blanket, which served for both bed and shelter, except, on rare occasions, where we took shelter beneath a bush or slept under a rail.“I presume no army ever went into the field and into battle more completely unqualified to perform intelligently the duties of soldiers and officers..”

The Confederate army, under the command of Beauregard, did not seem to dispute our advance at first, and abandoned the defenses at Centerville, retiring behind Bull Run.

On the afternoon of July 18th Tyler’s division encountered the enemy and the Blackburn’s Ford, where we had our first skirmish, in which the Second Wisconsin lost one man. Tyler's division did not gain a lodgment on the west bank of the Run and withdrew from the contest at that place. For the next two days McDowell’s army lay along the eastern bank of Bull Run, while he perfected his plans and prepared for a general battle. Beauregard stood on the defensive, and the sluggish waters of Bull Run wound their course between the opposing armies.

On Sunday July 21st, the first great battle of the Civil War, known in history as “The First Bull Run,” was fought, lasting about six or seven hours. Sherman's brigade had it very comfortable at first, and many of us thought our general was a born strategist. From our camp, near the Warrington Pike, between Centreville and Cubb Run, Sherman marched us down the Pike, crossing Cub Run, and arriving near the stone bridge, which crosses Bull Run, where he led us to the right into a grand old forest which, with its friendly foliage, sheltered us from the scorching rays of the July sun until about 11:00 AM. We held that position in fine shape (we could have held a longer) until Hunters division had made a wide detour to the right, crossing Bull Run at Sudley’s Ford, far up the creek, thus striking Beauregard on the flank and opening the battle with apparent advantage to McDowell. During the hours we held our position in the woods in the vicinity of Stone Bridge we were amused and encouraged by an occasional shot fired by a large 32-pounder smoothbore gun - the only big gun in McDowell’s army. This was planted in a commanding position near Stone Bridge, and for several hours Sherman’s brigade had nothing to do but watch the effect of the bursting shells thrown by it from time to time within the lines of the enemy."The Little Creole," P.G.T. Beauregard, received a hero's welcome after the First Bull Run despite being demoted to corps command the day before the battle. He was promoted to full general after the battle and immediately dispatched to the West (National Archives)

After Hunter struck Beauregard's left in the battle had waxed hot in that direction for an hour or two, some military genius discovered that Sherman’s brigade might be used to better advantage than supporting a one-gun battery on the safe side of the Bull Run, and forthwith we received orders to advance. Then Sherman moved his brigade at a double quick along the eastern shore of Bull Run for a mile or two. Once he halted us, not to rest, but to point us in late marching order, and to that end he ordered us to pile up our blankets and have our sacks in a convenient place by the wayside, where we it might return in camp for the night when the battle was over - then we knew of a certainty that he was a born strategist, or, if not at that moment, we knew it a few hours later when night closed in upon us and the whole brigade could not muster a single hard-tack, to say nothing about blankets.

After getting rid of our cumbersome blankets and useless provisions, we increased our speed, and shortly after arrived at Poplar Ford, pretty well fagged down, for the day was hot. At Popular Ford we waded the run, about waist deep in water, which was exceedingly refreshing. Once across the run, we moved over the fields in the direction of the Warrenton Pike, which we reached at a point in the valley where Spring Creek crosses the Pike where stood a stone house that was used for a hospital. From this point we moved up the hill eastward toward the stone bridge and went into battle.“ “It was said that Colonel Peck displayed superior leadership shortly after we went into the battle, by leading straight out to rearward...we took our hats off in his magnificent presence no more.” ”

Our brigade line extended across the turnpike and nearly at right angles with it, while the enemy seemed to be posted between our position and Bull Run. For a time, the battle seemed to progress favorably. The enemy was supposed to be in our front, but in the confusion that was not an easy manner to locate his position. When our line ceased to advance there was no well-defined battle line of the enemy opposing us, that I could discover, but we halted all the same, and continued to blaze away with our old smoothbore muskets.

About this time the smoke of battle became thick and the confusion great, and I lost all trace of General Sherman, not seeing him again until we had returned to the defenses of Washington. I also lost track of our Lieutenant Colonel commanding this Second Wisconsin. Our Colonel, A. Park Coon, was on General Tyler’s staff, and Lieutenant Colonel Peck commanded our regiment in his stead that.

Colonel Peck was calculated by nature for a great military leader. He knew the duties of enlisted soldiers and was aware of the fact that officers were created out of superior clay, and therefore, always insisted that soldiers should not forget to doff their hats when they came into the presence of their superiors. It was said that Colonel Peck displayed superior leadership shortly after we went into the battle, by leading straight out to rearward. Whether or not that report was true, I cannot say; but I know that I never saw our gallant lieutenant colonel again. He was not killed that day, neither was he wounded nor a prisoner of war, and he arrived safely in Washington at an earlier hour the next morning, but when we returned to our camp, later in the day, our Lieutenant Colonel commanding was not there to welcome us, and we took our hats off in his magnificent presence no more forever.This battle, called the First Bull Run to distinguish it from another fought on the same ground a little more than a year later, was never considered a very glorious affair, so far as it applied to the Union army. The strategy was deficient in some important particulars, but neither General Sherman nor his brigade were the only parties at fault.

Our battle losses, as compared with the wholesale slaughter of modern battles, prove that it was a small affair - a mere skirmish, but little fighting was done on either side. My regiment lost about 150 men and Sherman’s brigade sustained nearly 1/4 of the entire loss McDowell’s army, which was 401 killed and 1.071 wounded the Confederates lost 387 killed and 1582 wounded.The first shots of the battle were witnessed by Private Robert Beecham and the Second Wisconsin as they protected the stone bridge spanning Bull Run. In March 1862, the bridge was destroyed by the retreating Confederate army after evacuating their camps in Manassas. (LC)

The retreat began sometime during the afternoon, probably about 4:30. I never learned just why we retreated, and I'm not sure that anyone knew. It began in this way: After blazing away with our kicking muskets until the exercise became monotonous, we ceased firing and fell back down the hill to the Creek that ran through the valley, to get a drink. While there we leisurely filled our canteens. Then, as it was getting toward night, it occurred to some of the boys that our blankets and haversacks were not safe where we had stored them, or would not be after dark - besides, we would need our haversacks about supper time, and our blankets before retiring for the night, and they concluded that would be the proper thing to do to go back and get them, and back they started. Some historians say we ran, but that's false. There was no enemy insight - nothing to run from, and nothing to run after, except our supper in beds, and it was not likely that we ran for fun, but it seemed easier to retreat than to advance dash it generally does on the battlefield.In retiring from the field, we recrossed Bull Run above the Ford where we crossed it in the morning, but struck the Warrenton Pike again between stone bridge and cub run. When I reached the bridge over the latter stream, lo and behold! There was that big 32-pounder that Sherman’s brigade had supported so gloriously all the forenoon, broken down and abandoned in the center of the highway, blocking the crossing of the bridge. Behind the gun along the turnpike stood a whole battery, guns, caissons and all, in complete order, but no horses and no artillery men. I learned, later, that the artillerymen had taken their horses down to the run to water them and soon after returned for their battery, which they secured alright, in fact, never intended to leave it there; but the old 32-pounder was not removed from the position where I last saw it as I crossed the bridge over Cub Run, until it was removed by Beauregard’s men a day or two later. This was the source of great rejoicing on part of the southern confederacy for months after. In capturing that old gun, which was of less actual value on the field than one must get well handled, Beauregard thought he had won the independence of the Confederacy.This photograph captures the brass band of the Second Wisconsin Infantry as they appeared in 1861. By the beginning of 1862, the band had been reduced to fewer than sixteen musicians, in line with the typical downsizing of regimental bands during that time (Wisconsin Historical Society)

I reached our old campground, west of Centerville, a little before sunset, but the ground was all that remained to us; for on our return trip from the battlefield we missed the locality where we had so carefully stored our blankets and haversacks at the request of General Sherman, and we were truly orphans in a strange land.

While we were preparing our campground for a night's rest, who should dash along the pike headed towards Washington but a whole brigade or division of congressmen and newspaper correspondents, who had gone out with the army and carriages to see the fun, and, having seen enough to satisfy them, were going home. Most of them had lost their carriages and were mounted on horseback, having left the harness on just as they unhitched, in order that they might have something to cling to, and they were clinging fast enough. There was one newspaper man in the division by the name of Carleton, who wrote a great deal about the battle and the retreat afterward, having reviewed the battle from afar, as he “stood on the roof of a house near stone bridge.” I believe he lived in New York, for some of the 69th boys seemed to recognize him, and as the cavalcade dashed down the pike, one of them remarked to a comrade, as he pointed out a gallant horseman with a huge roll of manuscript in his pocket and a bunch of quills over his ear, while his soft felt hat stood for a saddle: “do you mind that foin-looking late lad and lads on the whole gang there Barney? Well that's Carlton, he writes for the papers and is one of the raciest correspondents in the army.” To which his comrade may reply, “begore Pat I believe you right he's the racist of that gang at events.” I'm not sure that Carlton soft felt hat felt soft, but it must have been some improvement on the bare back of a harnessed steed.

We cheered and laughed till the tears ran down our cheeks as long as the cavalcade was insight, and to the day of my death I shall never be able to recall the vision without laughing. During the retreat from Bull Run, the sight of Charles Carleton Coffin, a well-known war correspondent, in a panic-stricken state, offered some much-needed comic relief to Robert Beecham. "I will never forget that sight without bursting into laughter," he recalled. The National Tribune published this illustration as it serialized Beecham's account in 1902.

This cavalcade reached Washington early the next morning, safe and sound, but a little sore. From them it leaked out and gradually worked into the papers that “McDowell's army was panic stricken!”

We had settled for the night in our improvised camp when we were aroused by the bugle call which sounded fall in. It seemed that a council of war had been called by General McDowell, which, by common consent, had resolved itself into a council of retreat, where it was soon decided to begin the retreat to the defenses of Washington that night; in fact, there is nothing from McDowell to do but retreat, as they terms of a enlistment of half his army would expire within a week. There is no time to issue rations, and General Sherman obtained leave to put his brigade in the advance, next to the congressional and journalistic cavalry, as his men were minus blankets and provisions and some of them being three-year troops, their lives were worth saving. We learned, also in that mysterious way through which knowledge is often gained in camp, that General Sherman had this very retreat in contemplation when he instructed us to pile our blankets and haversacks on the Bull Run, so that we might be laid afoot and fleet as the wind for the home stretch.

Sherman's brigade took its place in advance of the infantry, and during that memorable night march we would have kept in sight of the flying calvary, but for thick darkness that concealed them from view. Soon it began to rain, a gentle mist at first, then a drizzle, and by daylight it was coming down in fine shape. On our homeward march we did not sing as much as we did on the advance, but we made better time period in fact it was the old camp before breakfast, after which we might sing again

We reached camp in sections, from 9:00 to 11:00 in the forenoon of July 22nd and I had the honor of being among the first. Our comrades who remained behind in charge of the camp, had caught a glimpse of the congressional calvary an hour or two earlier in the day, and heard the voice of Carleton as he shouted in passing: “the whole army is panicked stricken.” Then they put on the camp kettles and prepared coffee and hard tack and such other articles of food as they could obtain, for our refreshment. Immediately after breaking our 24 hour fast we seem to hear a voice of command saying: “to your tents oh Second Wisconsin, and we got there.”

When we retired to our tents, we hoped to enjoy season of sleep and repose, after our long and weary march; but about noon we were aroused from our slumbers, not to partake of a nicely prepared dinner - no, and really I never learned exactly for what purpose we were aroused. I intended to ask General Sherman why it was, but the general left us and went west before I found the opportunity. However, we received orders to gather up everything we possessed, and forming in line, we abandoned our camp and were marched to Fort Corcoran, where, we stood around in the rain and mud all the afternoon, while our unoccupied tents, only a mile away, were supposed to be in such dangerous proximity to Beauregard’s victorious army, the advance outposts which reach Centreville sometime the next day. That our wise general deemed it prudent to sacrifice our camp, if necessary, but to save the fort at all hazards, that was the grandest display of military sagacity that came under my notice during the war.

About 100 yards distant from Fort Corcoran there stood an old barn from which the weather boarding had been stripped, the frame and roof were still intact. As he shades of evening began to gather over the hills of Virginia, the orphans of the Second Wisconsin began to gather beneath the roof of that lowly asylum, which afforded us not standing room for all, but even a prospect to shelter with some relief from the pelting rain. It did not seem possible that General Sherman, or whoever might be in control of affairs, would keep us standing around there all night. The strategy of leaving our blankets and provisions on the banks of Bull Run was hard enough, but leaving our comfortable tents unoccupied, only a mile away, we stood out in the rain or crowded into an old dilapidated barn for shelter the live long night, seen beyond reason. Therefore, I stood outside with two of my teammates, without making an attempt to secure shelter beneath the crowded roof, until almost dark, hoping that we would either be marched back to our camp or order our tents brought up. Finally, I said to my comrades: “boys we must hunt cover.” A few yards from where we stood the end of an old plank protruded from the barnyard filth, which lead we followed and quickly unearthed not one, but two very dirty, but sound substantial planks, foot or more in width and about 16 feet long. To clean these planks was but the work of a moment, but to elevate them into the lofty from being to beam above the heads of our comrades crowded therein like sardines in a box, was not so easily accomplished. With us, however, it was no roost, no shelter; and after a victorious push we succeeded. Then drawing up our guns, cartridge boxes and other meager belongings, we perched ourselves upon our improvised balcony in the shelter of that old roof tree, like birds of paradise in the green branches, above and beyond the reach of the alligators and anacondas of the Amazon. Perhaps we did not enjoy that night of peaceful rest, we three who were above the clouds, so to speak. If Beauregard’s army had penetrated our lines at night and had to run up against us, we were in a position to fix them plenty. On the whole, our position both for comfort and for defense, in case of an attack, was far ahead and greatly more strategic than it could possibly have been had we remained in camp.

The next morning our quartermaster hustled around and found a few boxes of heart attack and some Switzer cheeses, upon which we breakfast. About 10:00 the rain ceased, and a scouting party that had been sent out to reconnoiter returned and reported that our camp had not been captured by Beauregard during the night, but was still standing, where we left it. Then a party with teams was detailed to bring up our tents, and we established camp in a position where we could protect the fort. After that we put our camp in order and began in earnest to prepare for war.

Two days later, I think, on the 25th of July, Abraham Lincoln, in company with Secretary of State Seward, visited the army in Virginia, on which occasion I had the opportunity of seeing the president for the first time. Mr. Lincoln was then in the full strength and vigor of manhood, and although he was not what people would call a handsome man, there was stamped on his face a fresh, vigorous, healthy and courageous look that inspired confidence. We had just suffered a severe and humiliating defeat, and the discouraging fact was beginning to appear plainly that we had on our hands a Great War that would require every resource of the nation to prosecute to a successful issue, and we certainly needed some encouragement. It was good to be impressed with the fact that the president on whose shoulders rested this mighty burden of war, with its vast train of results, either for weak or for woe to the people of a hemisphere, was not discouraged with the outlook.

Mr. Seward stood up in the president's carriage and made quite a speech to the soldiers, and which he gave us plenty of taffy; but Mr. Lincoln did not make a speech; He only said in a mild, gentle way, that he had confidence in the ability of the patriotism of the American people and their volunteer army to meet and overcome every enemy of the Republic, and to reestablish the government and flag bequeath us by the fathers in every part and portion of our country.

The soldiers gathered around the president's carriage, all anxious to shake hands with him, and they kept him handshaking until he must have been extremely tired. I felt like shaking hands with Mr. Lincoln myself, although not given to demonstrations of that kind in a crowd, but on second thought it seemed best not to assist in wearing the poor man's life out, so i did not offer my hand, and never had the opportunity to shaking hands with him.

During the years of war that followed I saw Mr. Lincoln many times, and every time I noticed that the lines of care upon on his face grew deeper, as the burden of war became heavier from month to month and from year to year.

Shortly after this visit from the president, General Sherman went west, to assume some higher command than a brigade, and I did not see him again until years after the war. Sherman became a great commander and strategist before the war ended, as every man of his old brigade knew he would from the moment he gave us the order to dump our blankets and rations on the banks of the Bull Run.

Extra Feature of Hardtack Illustrated

I met General Sherman once after the war, sometime during the early 90’s, at a national encampment of the GAR held in the city of Milwaukee WI. There was present at the time a great gathering of people, especially ex-soldiers of the civil war, from all over the country, who were holding reunions galore. There were unions of armies, of course, of divisions, or brigades, of regiments and of companies. There were reunions of the survivors of campaigns, of the survivors of battles, of the survivors of prisons and the survivors of hospitals. So, on meeting General Sherman at that encampment, I suggested to him that it was an opportune time to hold a reunion of his old brigade. That if he, as its old commander, would issue a call, surely it would enthuse every member of that grand old organization present in the city. But really, the general seemed not at all interested nor pleased with its suggestion. He said that “notwithstanding the fact that he himself would greatly enjoy such a reunion, he thought it quite impossible after the lapse of so many years to get a sufficient number together to make such reunion interesting.” I suggested that the lapse of the years was not wider in relation to Sherman’s than any other brigade organized in 1861, but, if he feared such a reunion would be too small to be pleasant, he might make the call for a union of the survivors of the first Bull Run, which would not fail to draw a large attendance.

At this point the general begged that I would excuse him for an hour or two, as he had an important engagement, but he would see me later, and in the meantime, I might look around among the comrades and learn about how many Bull Run survivors I could find. Of course, I excused the general, and he left me - he also left me with a lingering suspicion that he was not very enthusiastic over the reunion idea; at least, so far as it related to Sherman’s brigade or the survivors of Bull Run; but, hoping that he honestly wanted my assistance in this matter, I inquired diligently, as he'd suggested, with the result that I was unable to find a man outside my own regiment who participated at all in that “First Campaign” - that is on the union side. I found 75 or 80 ex-Confederates there, every one of them laid great stress on the fact that he was a survivor of the first Bull Run.

Among the boys of my old company and regiment I found a dozen or more, who were on the sick and convalescent list, and guarded and held our camp near Fort Corcoran during the Bull Run Campaign, and who remembered distinctly the fagged and furloughed appearance presented by those who returned from the battle on the fore noon of July 22nd 1861; but when I suggested the propriety of holding a reunion of Sherman's brigade, as our old commander was then with us, they replied “aren't you a little off? Sherman commanded in the West. We were never in his brigade.” The upshot of it all was, we held no reunion of Sherman’s brigade nor the survivors of the first Bull Run. What is more, I did not again meet General Sherman, for he seemed to have other and more important business on hand. If he was ashamed of his old brigade and the part he took in our first campaign, so far as I was able to discover, the feeling was reciprocated.|

Since the encampment I presume I have met thousands of ex-Confederates who were survivors of the first Bull Run and could tell me more of its glories than I dreamed it possessed. No wonder we were beaten. The Confederates were all there. But never in all these years have I met a Union soldier who was there and am therefore convinced that they have all passed over the dark river. Now General Sherman is dead also, and on the Union side I am, when I hope to remain for many years to come, the sole survivor of our first campaign.credits: This excerpt of Robert Beecham's memoir appeared in the National Tribune, a popular newspaper followed by veterans, in the August 14, 1902 edition.